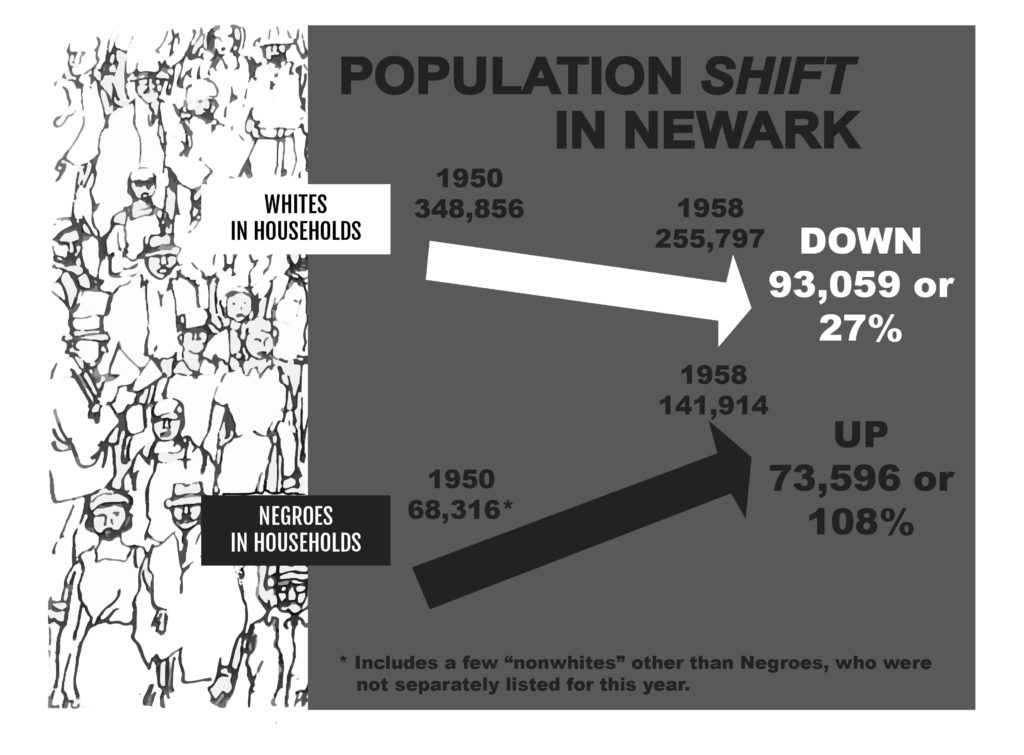

When the Mayor’s Commission on Group Relations released its 1959 landmark study, Newark: A City in Transition, its most momentous conclusion was captured by a U.S. News & World Report graphic: a white arrow pointed downward, a black one upward. They didn’t quite meet, but it was clear they would soon cross. When they did, Newark would become one of the very few majority-black large cities in the United States and the first in the northeast.

Since the first wave of migrations to Newark earlier in the century, the black population had largely consolidated in the center of the city in sections that would later form a large part of the Central Ward. But A City in Transition also revealed that, over the course of the 1950s, the population had begun to spread, especially to the south, across Springfield Avenue and down into the Clinton Hill neighborhood. Large swaths of the city’s center were growing increasingly black. But just as important as the sheer numbers was the growing political consciousness that it inspired: those numbers should have translated into greater political power, but had done so in only very limited ways. It would take a movement to build such power – it wouldn’t simply be given – and the medical school proposal helped spark one.

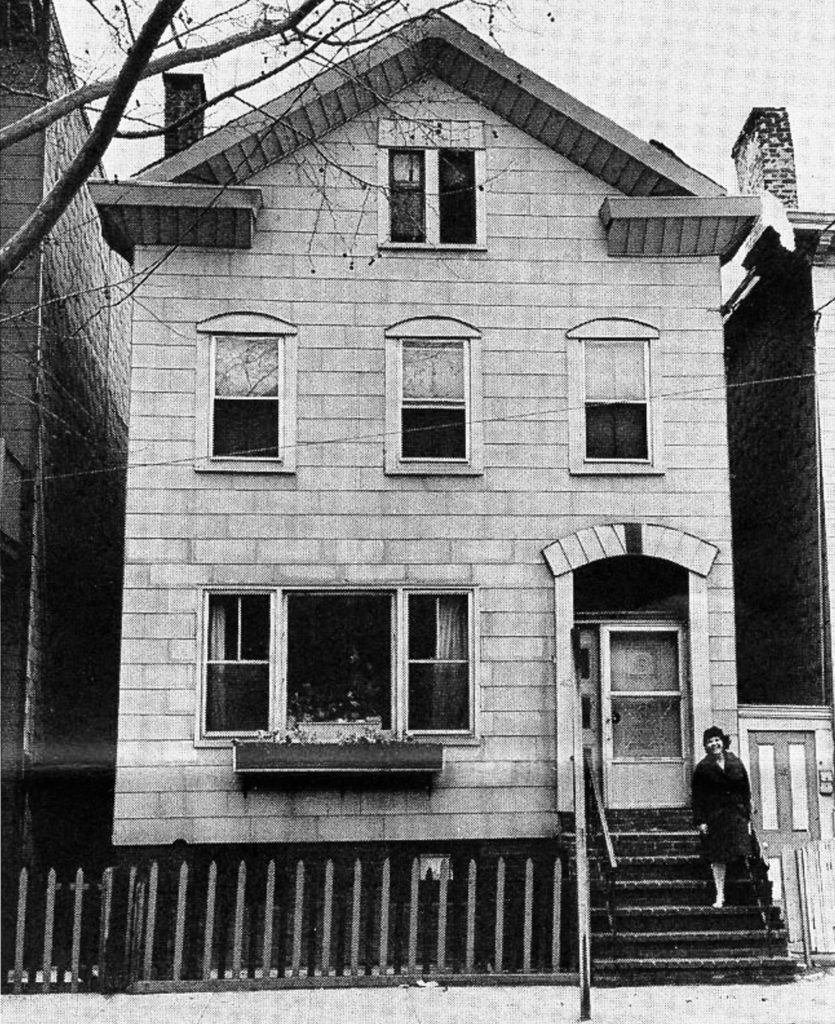

Mrs. Louise Epperson lived at 40 12th Avenue in a single-family home she had recently purchased and given a fresh coat of paint and new windows. So it was with no small amount of shock that, getting the papers in one morning, she noticed a front-page story that claimed the state medical school was moving to Newark and that the city had promised the land she lived on for the campus. She ran inside, picked up the phone, and called her neighbors. “Get up and get your paper from the door” she told them. “Did you know that the medical school from Jersey City is about to move to Newark and take our homes?”

The group that eventually grew from these phone calls, the Committee Against Negro and Puerto Rican Removal, was the first sign of grassroots opposition to the medical school relocation plan. Epperson explained to a local newspaper that the committee was not opposed to a medical school in Newark, but to the razing of a residential neighborhood for that purpose, especially so close to available urban renewal land.

“The Negro has invested a lifetime of hard work in the present and future of this city. He has earned the right not to be uprooted to satisfy the political ambitions of a few unscrupulous politicians.”

Louise Epperson

At a subsequent meeting of about eighty site residents and concerned citizens at Newark’s Longshoremen’s Hall, other committee members, like Central Ward Democratic chairman Eulis “Honey” Ward, called attention to the dangers of reduced ratables and increased school crowding should the site’s population be moved elsewhere in the city. Epperson and others hammered at the threat to the black community’s political power. The medical school relocation, they argued, was an attempt to break up an increasingly significant black voting bloc.

The municipal administration, meanwhile, was preparing its own arguments, and over the next few months public discussion would take some unexpected turns. The administration bolstered its case for the medical school with a door-to-door survey of site residents conducted by inspectors from the municipal Department of Health and Welfare. They concluded that 96% of all structures in the area were deteriorated, that 89% of the houses were substandard, and that each housing unit in the area was within a half-block of a tavern, junkyard, empty lot, burned out building, or other nuisance. Of the 831 families interviewed, 708 said they were not opposed to the city moving them elsewhere.

The city was demonstrating a “total disregard for the uprooting of more than 8,000 families and businesses already experiencing a powerlessness peculiar to Negroes in urban ghettos.”

Members of the Committee Against Negro and Puerto Rican Removal, though, argued that the survey was a farcical version of citizen participation comprised of loaded questions that presented the college relocation as a done-deal. Therefore, most residents would of course be in favor of the city providing them a new place to live. The city was demonstrating, said a local elementary school teacher (who did not, however, live in the proposed medical school site), a “total disregard for the uprooting of more than 8,000 families and businesses already experiencing a powerlessness peculiar to Negroes in urban ghettos.”

When Mayor Addonizio called a public meeting on the first day of February 1967, residents of the medical school site and their supporters did not speak with one voice. Some waged an outright attack on the plan, including one resident who had worked on the mayor’s recent reelection campaign and felt betrayed by the impending destruction of her neighborhood. LeRoi Jones charged the mayor with trying to “remove the political potential of black people.” Others expressed concerns about the ability of the city to re-house them in other parts of the city, but did not condemn the medical school relocation itself. One neighborhood store owner said she would be glad to see the neighborhood go because “I’m afraid to open my doors,” and two local clergymen praised the potential educational opportunities and questioned whether the neighborhood was really worth holding on to.

The city’s federally funded antipoverty agency, which had already publicly condemned the medical school plan, decided to settle the issue once and for all. Known nationally for its independence and tense relationship with city hall, the United Community Corporation (UCC) dispatched a team of canvassers to the medical school site. They spoke to 372 residents, a third of whom lived in the first-phase land guaranteed to be available for construction the following spring, and two-thirds of whom lived in the 100 acres promised for subsequent phases of construction. The results surprised them. Fifty-three percent of total respondents favored bringing the school to Newark even if they had to move to accommodate it. While the percentage dropped to 45% in the first-phase area, the study’s director conceded that the expected groundswell against the medical school had not occurred.

The marketing research center that examined the survey results concluded that “the population appears to be resigned to the necessity of doing what it is told to do. There is little active resistance to the necessity of uprooting oneself.” They did find, however, “a high degree of skepticism and cynicism” regarding the motives for building the medical college in the Central Ward. While the survey did not provide the hoped-for repudiation of the medical school deal, it did sharpen the philosophical debate opponents were forcing on the city administration. Though some UCC trustees continued to oppose the plan altogether, the majority approved a resolution deploring the city’s methods and demanding that Addonizio “take the necessary steps to acquaint, inform and involve the people in the decision making processes” for all future projects.

If city officials had expected a smooth road, however, the first public blight hearing on May 22, 1967, quickly disillusioned them. In order to qualify for federal dollars, urban renewal projects had to target “blighted” land. In Newark, the Central Planning Board, composed of mayoral appointees, handed down blight declarations as if their determination was a foreordained technicality. There could be little doubt as to how the board would rule on the proposed medical school land. The mayor, after all, had already guaranteed the land’s delivery and the city council would soon approve the contract with the medical school. But from two minutes in, when “a woman in the second row, wearing a crescent pin,” as a local reporter described her, pelted board members with three eggs, this hearing proved to be atypical.

The head of a UCC work-training program warned that “there’s a storm coming over the city of Newark and hell and his brother couldn’t hold it back.”

The eggs stopped, but charges and countercharges flew. Colonel Hassan Jeru-Ahmed, the self-styled leader of the Blackman’s Liberation Army, argued that the planning board’s racial imbalance rendered it illegal and called the proposed land-clearing a “political move to get rid of Negro votes.” Harry Wheeler, a local schoolteacher and UCC trustee, called the hearing “a mere façade to rubber stamp what has been negotiated.” The city housing authority’s director of relocations provided a cheerful history of urban renewal projects in Newark. The city fire director recommended that “the area be demolished whether a medical school is built or not.” And at about 10:30 p.m., Colonel Hassan stormed the stenographer’s desk, ripped the transcript from the machine, and tore it up. Soon after, one of his soldiers threw the recording machine against the wall where it smashed to pieces, and the hearing fell into chaos. Amidst chants of, “Hell no, we won’t go,” the meeting was hastily adjourned.

The Central Planning Board scheduled another hearing just two days after the first. But with sixty-five picketers circling the pavement outside City Hall, city officials called it off and rescheduled it for three weeks later. The outcome of this final blight hearing surprised no one. It took place after the city council had unanimously approved a contract promising the initial acreage for the campus center would be delivered within the year, and the additional 100 acres within eighteen months of any request from the medical school. At that council meeting, Robert Curvin of CORE told the city council that the contract constituted a “gross example of racism,” and the director of the UCC’s Legal Services Project called it illegal since blight had not yet been declared. A white UCC aide told the council, “If you build or try to build the medical school there will be violence.”

Despite such warnings, Mayor Addonizio signed the contract immediately after the city council approved it, and the college trustees added their signatures the following day. The Central Planning Board declared the land blighted, and the juggernaut rolled on.