“They had already blighted part of Twelfth Avenue where I lived, and one side of the street was blighted. And they called that urban renewal. Well I say it looks more like nigger removal than urban renewal…”

LOUISE Epperson

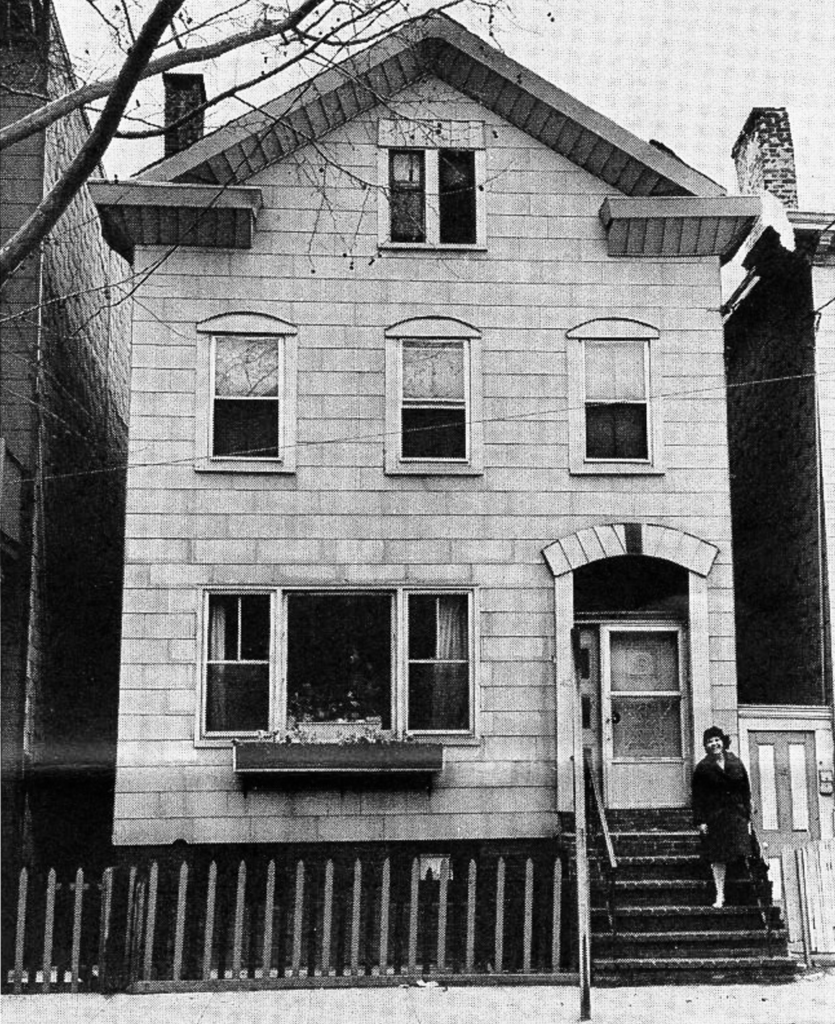

Twelfth Avenue Blighted

Louise Epperson was born in Waynesboro, Georgia in 1908 and moved to Newark in 1932. She came North to live with her sister, a dancer who worked in New York City. Epperson’s mother and father, a restaurant owner and a barber, upon discovering the profession of their eldest daughter, had forbidden Louise from seeing her. A young woman who left home for the nightlife of the City was not their idea of a respectable role model. Louise moved in with her sister anyway.

Shortly after arriving in New York, Epperson moved to Newark to live with her aunt who owned the first tavern to open in Newark after Prohibition ended. She lived a quiet life early on, first on Orange Street with her aunt and later in her own place on James Street. Although not as “elaborate” as her aunt’s place, she still had a toilet with running water and so counted herself fortunate. Most important to Epperson was that she had a place of her own.

During the Depression, inspired by President Roosevelt’s Works Progress Administration and its emphasis on collective self-determination, Epperson began to assist people in her neighborhood in finding work. Securing a job was not a simple task for Black residents of 1930s Newark. Epperson herself first worked as a domestic for a White family outside of the city. She was “holding” a job for a friend who was looking for a better position. This was the first time Epperson had ever been in a white person’s home and at first she thought it meant she was “comin’ into somethin’.” But Epperson did not like the family, so when her friend came back for her job she went to work for a family who lived on Roosevelt Avenue in Newark. The head of the household was a Dr. Swain.

By day she worked as Dr. Swain’s receptionist in his home office, opening up at 7 am each morning. In the evening, Epperson would change uniforms and move into her domestic role, cooking the family dinner and cleaning up afterwards. While she liked the family well enough, it was not her intention to be a lifelong domestic. She finally secured a position as an aide at Willowbrook State School for the mentally disabled, on Staten Island. Once established there, she applied for a promotion as an occupational therapist, a job that she was told no African Americans were ever hired to perform.”You don’t know what they’ll hire until you try,” she told historian Mark Krasovic in a 2001 interview. “And I bidded [sic] on that job and I got the high score and I received it. And I was the first black to work on that–I was the first black to work in occupational therapy.”

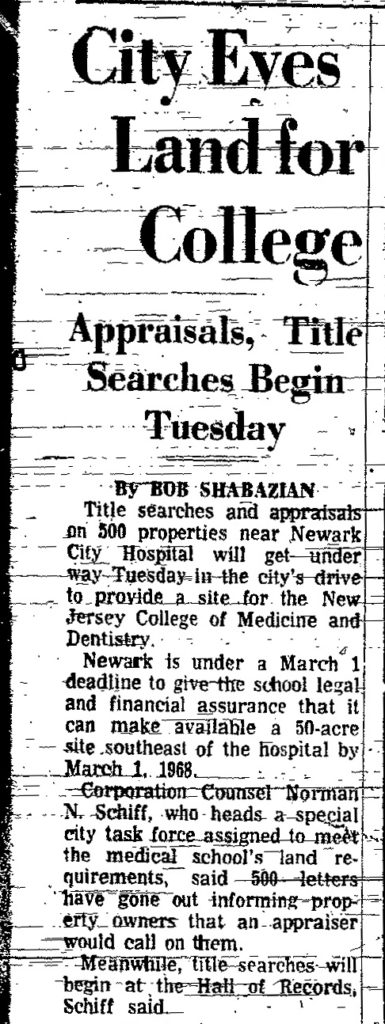

Assuming this would be her last job, Epperson planned to retire from the school in 1967. But on January 1, 1967, when she picked up her morning paper, Epperson read a headline that changed everything.

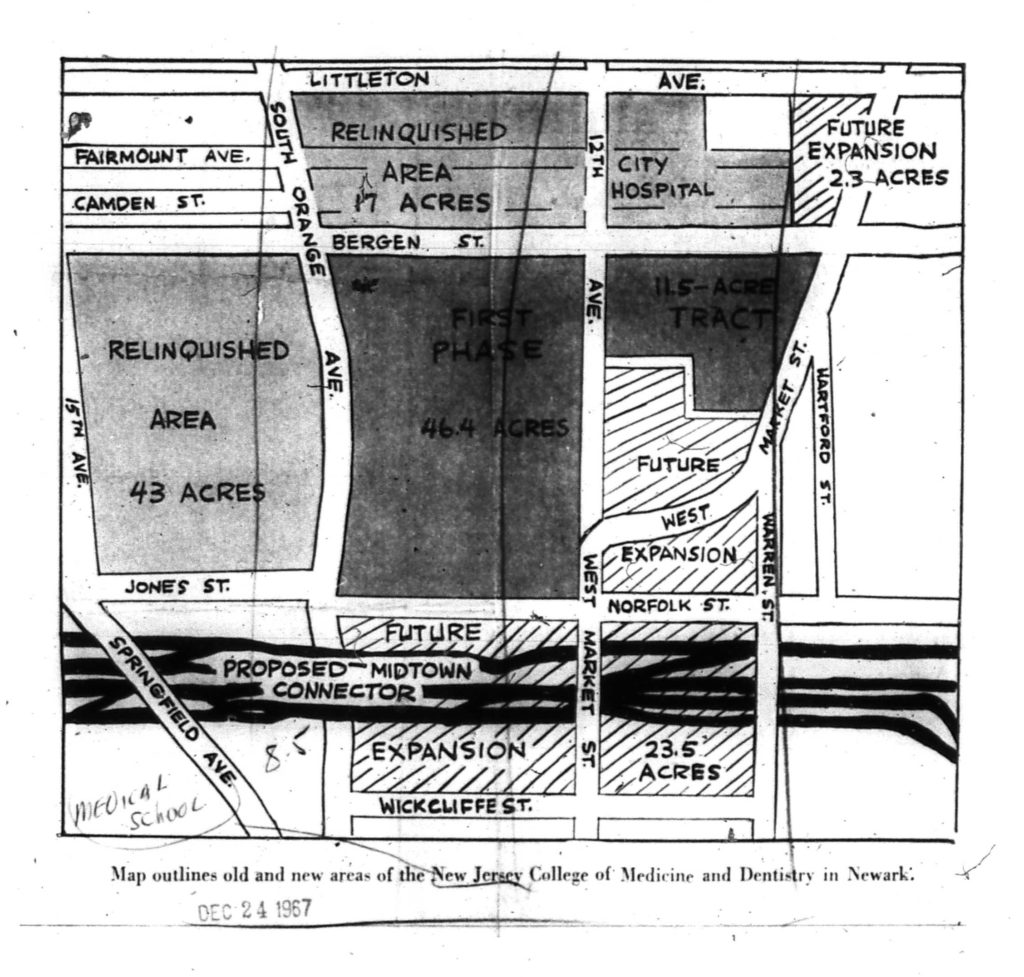

In 1965, the state of New Jersey had acquired The Seton Hall College of Medicine and Dentistry in Jersey City and renamed it The College of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey. Now CMDNJ was relocating to Newark. The state needed land on which to build the campus, and the newly named University Heights neighborhood where Epperson lived seemed perfect to them.

While Louise Epperson did not consider herself an activist, she had been politically active since her exposure to the WPA, and in 1954 she became involved in city politics, working on the campaign that succeeded in the election of Irvine Turner as the first Black Newark city council member. She also spent time canvassing for Harry Hazelwood, who in 1958 would become Newark’s first Black municipal court judge. Mrs. Epperson was also a regular guest on a local political affairs radio show called News and Views hosted by her friend Bernice Bass. Louise Epperson knew how to organize – and how to mobilize.

"I asked to see the Mayor. I asked for an audience with him."

What are you going to do for my neighbors?

Epperson’s tactics proved effective. The town meetings she called to discuss the CMDNJ “land grab” were attended by standing-room-only crowds. She garnered the aid of ministers who opened their churches to her and union leaders who offered her their halls when the churches became too small for the growing crowds. She took her message wherever she thought people needed to hear it, including the city’s go-go bars:

"I got up in the cage and I told them I couldn't shake, but I wanted to shake their brains up so they could know what was happening in Newark."

These are OUR homes!

She had helped create a groundswell whose momentum created the Committee Against Negro and Puerto Rican Removal. At the required council meetings grudgingly held by the Addonizio administration in exchange for promised federal funding for CMDNJ, the community showed up en masse.

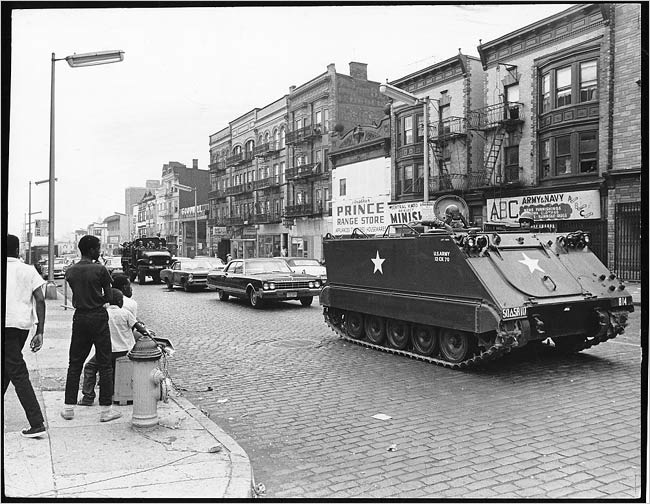

But before the public hearings on the medical college site could take place, Newark broke out in a rebellion.

The people who would not take Epperson’s calls prior to July 12, 1967 were much more amenable to talking by the time the National Guard started rolling out of town on the 17th of July.

Before the riots, Epperson was sent in circles; the governor told her that the hospital was a municipal concern, the mayor said it was for the county to decide, and the federal representatives in Washington said they could not get involved in “local” issues. But the six-day uprising gained national attention and Newark officials wanted to quell the notoriety that had branded the city a disaster zone. In addition, some in City Hall were just plain scared that another “race riot” would happen if they did not at least attempt to appear as if they were listening to the demands of Newark’s Black residents. The officials asked Epperson to “call them off.”

"I said, I can't call them off. I didn't call them on."

You did that, not me.

Testifying before the Governor’s Select Commission on Civil Disorder in December of 1967, Louise Epperson spoke plainly:

“I don’t care how many tanks, how many guns, how many K-9 dogs you get, I don’t care what the situation is, unless you plan to kill every black woman, man and child in this city it will not work. We must have housing.”

"I was in a very, very bad situation..."

These are the harassments they did to me.

In February of 1968, speaking on behalf of the Committee Against Negro and Puerto Rican Removal at the Medical College site hearings, Epperson painted a grim picture of the housing scene in Newark:

“… you say that we’ll have housing for these people to go into by the end of the year. By the end of the year, if we don’t all be dead, we’ll all be in jail. I’m going to tell you, Judge, all of the absentee landlords in the area have already sold their houses. The people are moving out. The vagrants are coming in. The houses are being set on fire every night. You don’t know if you are going to burn up alive or not, and the insurance people now refuse to take your money for insurance. You don’t know whether you are going to wake up in a blaze or not tomorrow. The bums are hanging on the streets, sleeping in all of these empty houses, where they’re wrecking and pulling out the pipes and things. Every night you can hear hammering all through the neighborhood…”

Activists take risks, and Epperson continued organizing despite what seemed to be threatening actions: her telephone was repeatedly cut off although she owed nothing on her bill; her heating system was vandalized, the lock broken and water poured into the oil; and her car windows were shot up – she found rifle pellets littering the ground. She began parking her car in front of the medical school so that people would think it belonged to someone associated with the hospital and not someone who was fighting its expansion. Still Epperson persisted.

Many others, though, were not as willing to associate themselves with the controversial battle against NJCMD. Try as she might Epperson could not secure a lawyer, “for love nor money,” to take the case against the hospital—at least not one who was affordable to a grassroots activists group. Even the house rent parties that she and her friends threw could not raise the fees required for the lawyers in question. It was just too much of a hot button issue for so many professionals who wanted to keep working in the city after the matter of the hospital’s relocation was ultimately resolved.

But the outrage sparked by a newspaper headline and channeled through the determined organizing of an occupational therapist had become a powerful community movement. New Jersey Governor Richard Hughes appointed Epperson to a Citizens Oversight Committee, and shortly thereafter CDMNJ agreed to many of the recommendations made by Epperson and the Newark community. The accord, known as the Newark Agreements, ensured that the CMDNJ campus would displace fewer residents by occupying a significantly smaller territory than the initially proposed 300 acres, and even less than the 150 acres secretly pledged by Mayor Addonizio in 1967. In addition, 60 acres were designated expressly for new housing.

Of course, there were still numerous families who suffered under yet another relocation in the name of “negro removal” as urban renewal was often called by those most affected by it. But thanks to the work of Epperson and a handful of other local activists, more people received more compensation for their homes than initially promised. In addition, extra beds were added to the hospital specifically to serve the local community and eventually the institution did deliver on some of its promised benefits, supplying needed medical services – and even some jobs – for the residents, and income for the city as a whole.

Epperson herself, however, was only paid $13,000 for a home that she originally had purchased for $20,000. This inequity was due to the fact that the neighborhood, as with so many others in Newark, had been designated as “blighted” by city officials, a label that was difficult to remove once applied. (Epperson had initially been offered a higher price for her home by the mayor himself if she agreed to stop campaigning against the hospital’s expansion. She refused the offer).

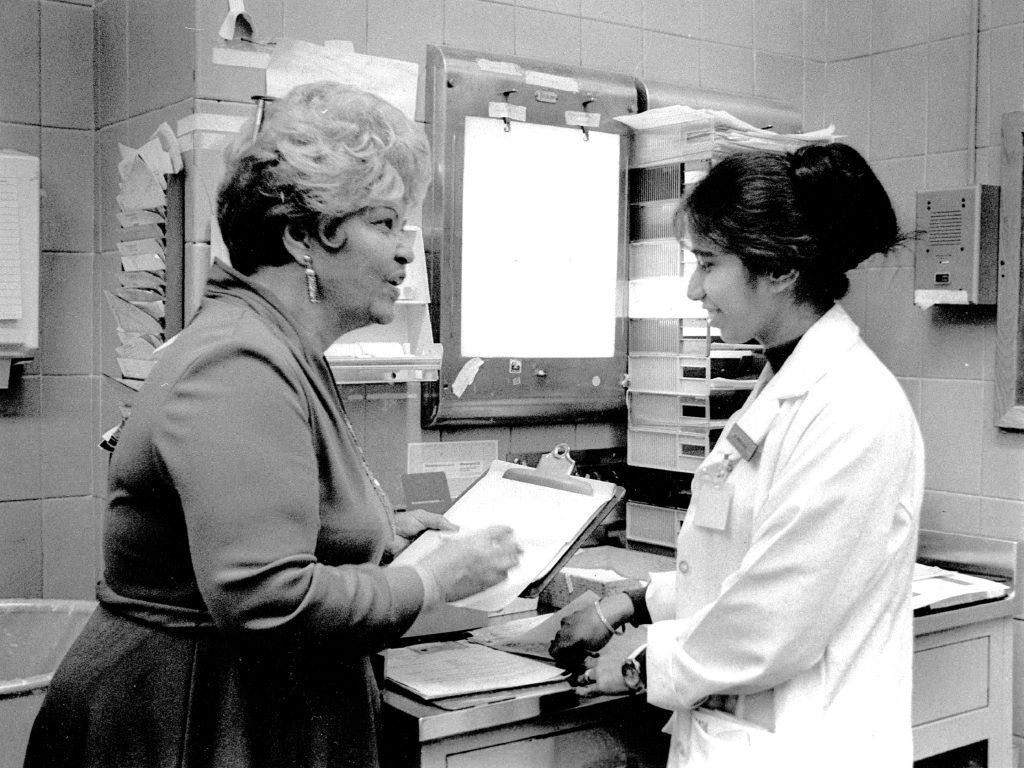

Epperson’s training as an occupational therapist and the reputation she had attained as a community organizer resulted in her becoming the first Black person – male or female – appointed to the Newark Board of Health. A measure of the respect that Epperson had earned was the offer of a job at the very hospital against which she had fought. Epperson had initially declined the offer, concerned that her fellow residents would mistrust her if she worked for the same institution she had spoken out against, but she ultimately accepted the position, which she used to create a patient relations program that advocated for her community and ensured that the hospital continue to be responsive to the needs of Newark’s residents:

“And people in the neighborhood today call me. [They say], Mrs. Epperson, you know what they’re doing up at the hospital? They did this to me and they’re doing this and they’re doing that… I say, Sweetheart, give me your name. You stay home. I’ll get in touch with you. I’ll go straight up to the hospital. I’ll say, ‘You know I’m coming because I just got some complaints on you, Dr. So-and-So. …You don’t treat people like that because you’re the MD.’

"…It’s like my home to me when I walk up there. And I tell them, I come with the chandeliers, the lights and everything else. I’m not going any place. I’ll be here. And I will be here …I worked until I was 87."

Louise Epperson