Less than two months after the UCC aide warned of impending violence in Newark, it arrived.

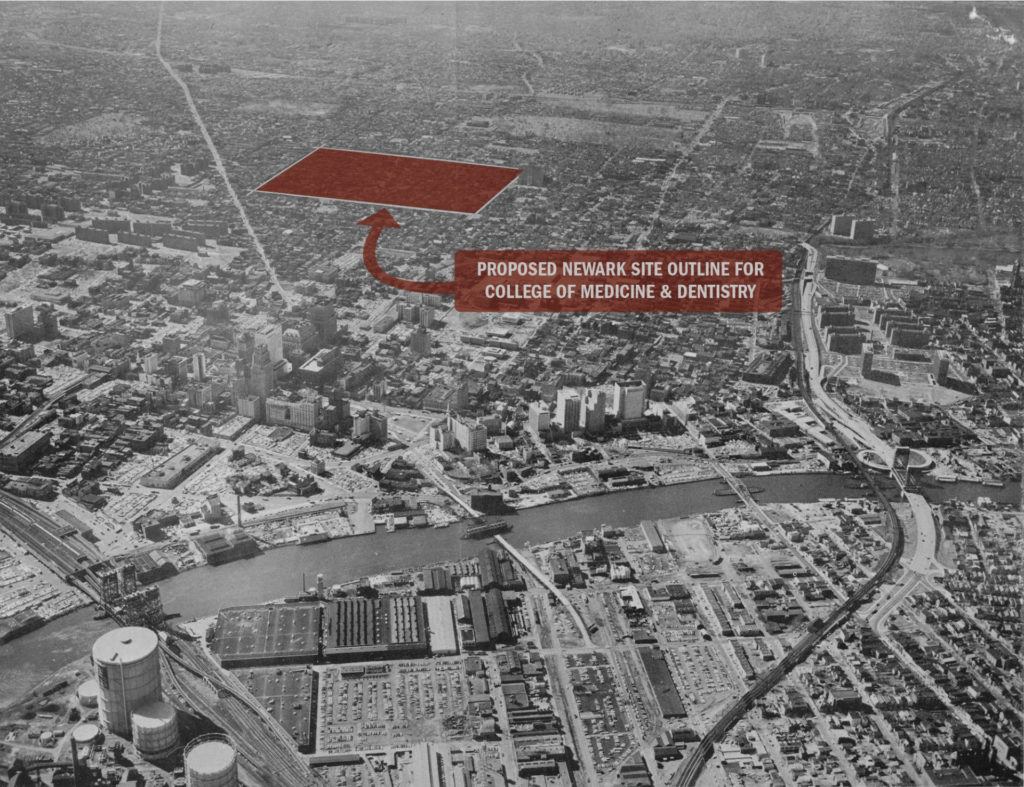

It’s hard to say with any great precision what difference the July 1967 riots made in the medical school controversy. The black rebellion suggested to many that community frustration over the proposal had reached a critical point. The deadly suppression of that rebellion by state and city forces suggested that local power structures were unlikely to yield. Indeed, that November Mayor Addonizio told HUD secretary Robert Weaver that the centerpiece of Newark’s Model Cities plan would be the school’s relocation to the Central Ward. After the blight declaration, the city just needed federal approval to reassign that new urban renewal land from residential to public purposes.

Meanwhile, neighborhood opposition to plan regrouped, reorganized, and brought in reinforcements. The most notable entrant into the controversy was the Newark Area Planning Association (NAPA), which was organized by a community organizer and law student named Junius Williams. NAPA and other opponents, calling the current plan “fraudulent” for overstating the school’s land needs and for not providing enough replacement housing, encouraged HUD to withhold all urban renewal funds from Newark. Before the year was over, their pressure produced a crucial concession: the medical school reduced the amount of acreage it was demanding.

Junius Williams said he’d grown tired of development driven by “some lone person sitting behind an agency desk, dealing and wheeling with the land.”

In January 1968, federal officials sent Governor Hughes a list of conditions the state would have to meet in order to receive the necessary federal grants. They included guarantees of adequate replacement housing, of employment opportunities for local residents, and, most importantly, community participation in the planning and development of the college.

In February, Governor Hughes announced a new series of public hearings. A team of community negotiators, composed of representatives from NAPA and the Committee Against Negro and Puerto Rican Removal, along with a few from the UCC and the Newark Legal Services Project, and backed up by crowds of community participants, met with officials from state and local government, the Newark Housing Authority, and the medical school to hammer out an agreement on the process by which the school might relocate to Newark. The issue of replacement housing was central, but community negotiators also pushed for long-term solutions to urban renewal’s undemocratic methods.

When Louis Danzig of the Newark Housing Authority balked at the inevitable inefficiency of a community-based process, Junius Williams said he’d grown tired of development driven by “some lone person sitting behind an agency desk, dealing and wheeling with the land.”

The time had come to change that.

The negotiations ended early in March with an agreement that was remarkable not only for the concessions (in terms of site size, job training opportunities, community healthcare services) it contained, but also for the mechanisms of community participation it established in what had seemed impervious to anything resembling democracy. The agreement recognized that “the low-income and disadvantaged sectors of the community” were now “prepared to share responsibility for the future” of their own healthcare. The media for their participation would include: a “Newark community health council,” containing nine community representatives, that would develop comprehensive healthcare plans for low-income residents; a Citizens Housing Council to devise a plan to rehouse those dislocated by the school; and a “review council” to assure that potential construction contracts stipulate that at least one-third of all journeymen and one-half of all apprentices building the new campus would be drawn from underrepresented racial groups. Residents of the Central Ward and their representatives now had some policing power over this massive urban renewal project.

Unfortunately, as it turned out, there was a lot to police. The juggernaut, in the end, wasn’t so easily turned, especially since it involved not only massive amounts of public money but also the racial recalcitrance of local labor unions. Construction began with cheap modular units on a small parcel of land on the north side of 12th Avenue. This “temporary” campus (the units are still there today) would be used until the larger permanent campus across the street was finished.

Though members of the construction review council objected, the temporary campus went up without the required minority apprentices and journeymen. Early in January 1969, members of the council demanded that federal officials study the workforce before releasing any more funds for campus construction. “We have been short-changed all the way,” one member said. “Until this situation is corrected, construction, in our opinion, is proceeding illegally.”

Despite such problems, construction began on the permanent campus that exists today in the early 1970s. The historic agreement that made it possible was implemented imperfectly, at best. Assessing it fully would require a complicated calculation of loss, preservation, and gain. Any assessment would have to consider the contribution made to black political power as it moved decisively toward city hall in the late 1960s. It would also have to consider what happened on the land that was not given over to the medical school. This is land where the New Community Corporation built its first housing development and, later, the first supermarket to be seen in Newark in decades. It is home to schools, churches, and businesses. Thousands of people live there. It is where Kea Tawana built her ark.

And still, there’s a fifty-acre medical school campus, now a part of Rutgers, in the middle of the Central Ward. The vision of a postindustrial Newark with University Heights at its center has largely come to pass, but on less land than originally envisioned. So perhaps the safest thing to say is that the medical school did indeed come to Newark, but in a way that just about everyone involved could claim some measure of victory.

What remains to be seen is whether the participatory possibilities that inhered in the black freedom struggle’s encounter with publicly funded development in the 1960s are at all available today, in Newark’s latest development boom. As they were fifty years ago, the people will be ready, I’m sure. State and private developers will have to meet them halfway.