The black and white film below is shot from the sky.

Made in 1966 to commemorate the 300th anniversary of Newark, New Jersey, it is full of housing projects, parks, cathedrals and airports. On the barren hillside, universities are beginning to rise from the dust.

The film’s narrator extolls a vision of urban renewal. The vision is of a once-proud city—New Jersey’s “greatest concentration of population and finance”—now grown “worn and blighted.” But not to worry, the ridiculously confident voice reassures us, the city is filled with people who have “the spirit and vigor to grow and build anew.” But there are no people to be seen in the film.

Where are the people?

This is Newark, 1966 delivers a flyover view of a historic city primed for a bright future. By 1970, we are told, Newark will receive one billion dollars in federal funds and commercial development; a larger investment in Newark, boasts the narrator, than in any of America’s thirty largest cities.

What happened next?

Well, not everything went according to plan.

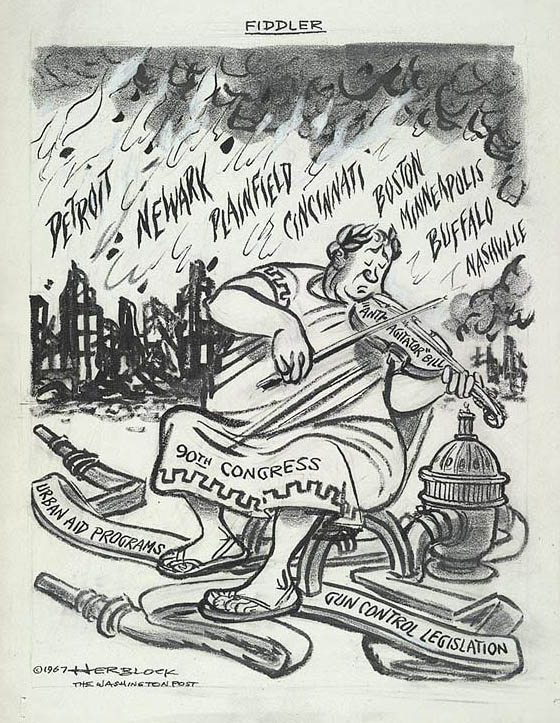

The year after the movie was made Newark was on fire. And it was not alone. Call them riots, rebellions, insurrections or civil disturbances—call them what you will—when the flames had subsided both Newark’s urban fantasies and the liberal vision of The Great Society had been charred beyond recognition.

White flight from Newark began in the 1950s, but any hope of stemming it went up in smoke in 1967. The Newark that emerged from the conflagration was not the one imagined by the civic boosters responsible for This is Newark, 1966. The mass exodus of the progeny of the European immigrants who had populated and financed Newark for much of its history, combined with political mobilization by African-American Newarkers, led to the election of Kenneth Gibson as the first black mayor of Newark in 1970.

The city Gibson inherited was not the one depicted in the film. In the wake of Newark’s summer of discontent, development money, businesses and tax dollars lit out for the suburbs. Newark was looted, abandoned and stigmatized. Needless to say, the promised billion dollars for urban renewal never materialized. By the time Gibson took office—bereft of resources—Newark was a decaying industrial city in an increasingly post-industrial society.

The deep economic recession of the 1970s was particularly devastating for Newark. Many of the people who could, fled the city. Many of those who remained were living at or below the poverty line. Cutbacks in education, jobs and public safety only exacerbated the lure and devastation of drugs, gangs and crime.

The low-income, high-rise housing projects celebrated in This is Newark, 1966 became poverty prisons. Many were demolished.

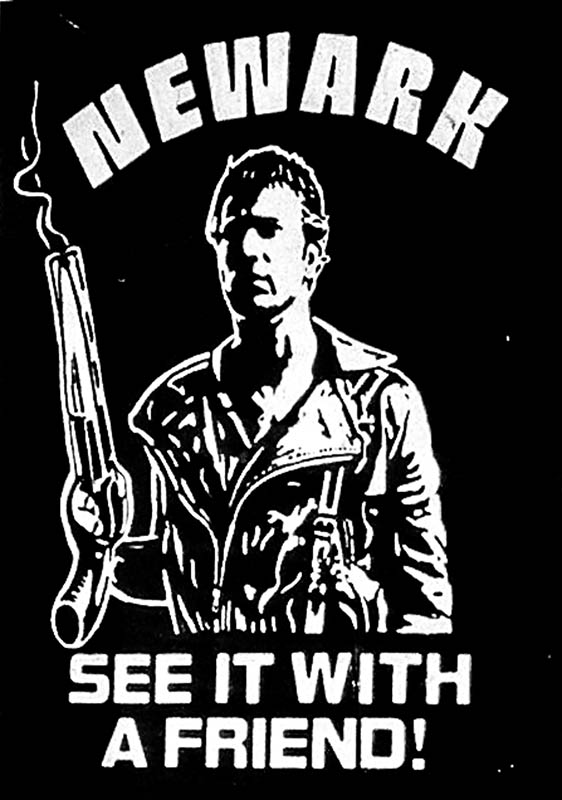

Images like this began appearing on posters, t-shirts and coffee mugs:

In 1987, the Scudder Homes went from this…

…to this.

The national media made Newark the poster child for the decline of urban America: the carjacking, gangbanging, dark night of the American city. One of the most devastating litanies of Newark’s sins was delivered in 1981 by Newark’s own Phillip Roth in Zuckerman Unbound, when his alter ego, Nathan Zuckerman, is taken to task by one of his readers for his nostalgic depiction of the city:

“What do you know about Newark, Mama’s Boy! Moron! Moron! Newark is a nigger with a knife! Newark is a whore with the syph! Newark is junkies shitting in your hallway and everything burned to the ground! Newark is dago vigilantes hunting jigs with tire irons! Newark is bankruptcy! Newark is ashes! Newark is rubble and filth.”

But there are different, more complicated stories one could tell about Newark’s past. For example, the film did get a couple of things right. Perhaps the most prophetically accurate prediction from This is Newark, 1966 was the vision of Newark’s future as a university city.

In the world of Newark, 2016, six universities and community colleges serve 60,000 students in a city whose non-student population decreased from 405,000 in 1960 to 275,000 by 1990, where it has pretty much remained until now.

Newark’s emergence as a hub for higher education in New Jersey has been an undeniable boon for the students who have earned degrees and for the city as a whole. But what about the people who are never seen in the film and who stayed in Newark after 1967? What did the transformation of Newark into a college town mean for them?

In 1966, in anticipation of all that urban renewal money, the film’s camera hovers over the newly minted “University Heights” neighborhood being cleared for development.

But what cannot be seen from the film’s birds-eye view of University Heights is the people who live in the neighborhood; the very people who will soon be displaced by the arrival of the College of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey (CMDNJ) in their neighborhood, the people upon whose land the medical school campus will be built.

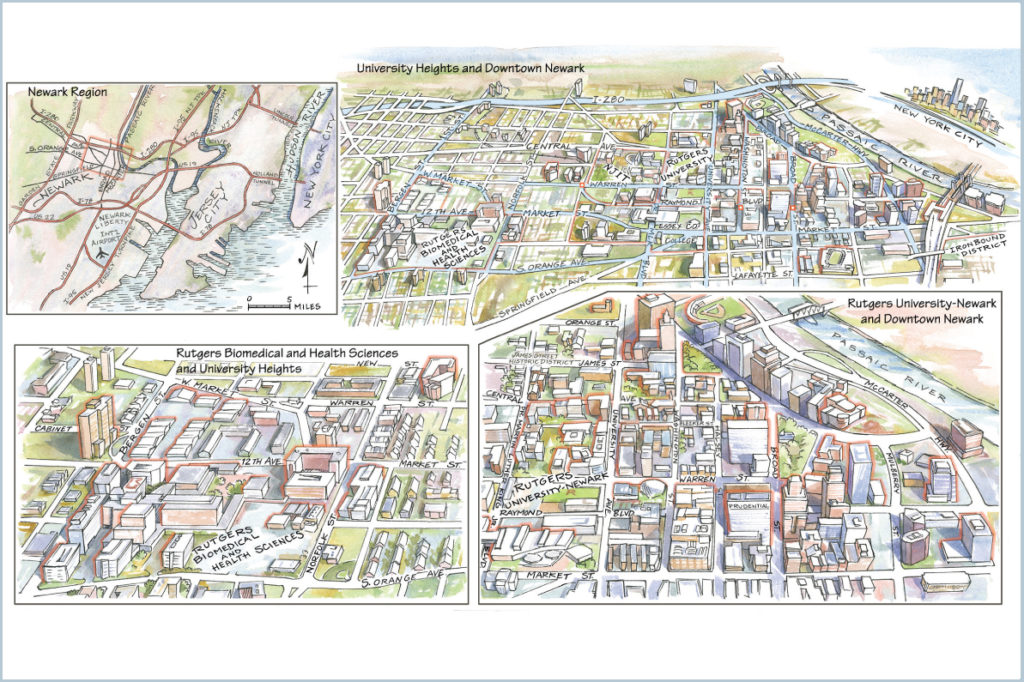

Today, University Heights is home to Rutgers University-Newark, the New Jersey Institute of Technology, Essex County Community College and, just beyond the top frame of the 1966 footage, Rutgers Biomedical and Health Sciences and University Hospital, the current occupants of the CMDNJ campus.

Here’s what University Heights looks like now:

With the 50th anniversary of the “riots” looming in 2017, and as Newark embarks upon its most ambitious wave of urban renewal since the mid-1960s, what might we learn from the city’s last vision of unbridled real estate optimism and the people it rendered invisible?