Midcentury politicians, especially in heavily industrialized regions, had much to deal with. Increased migrations – of people, capital, businesses – in and out of their cities and states forced them to reimagine the foundations of prosperity and the provision of services for their constituents. One piece of this larger reimagining was what is now often referred to as “eds and meds.” But in New Jersey, it was a long time coming. In 1954, voters rejected a bond issue providing for the establishment of a state medical school, and so the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Newark stepped in. It established the Seton Hall College of Medicine and Dentistry and found a home for it in the bloated, cavernous Jersey City Medical Center, an aging vestige of the alliance between New Deal funding and local machine politics. But over the course of the next decade, the church struggled to tame the beast and ultimately determined that its continued involvement with medical education was untenable. In late 1964, Governor Richard Hughes, spying an opportunity, announced the state would purchase the college.

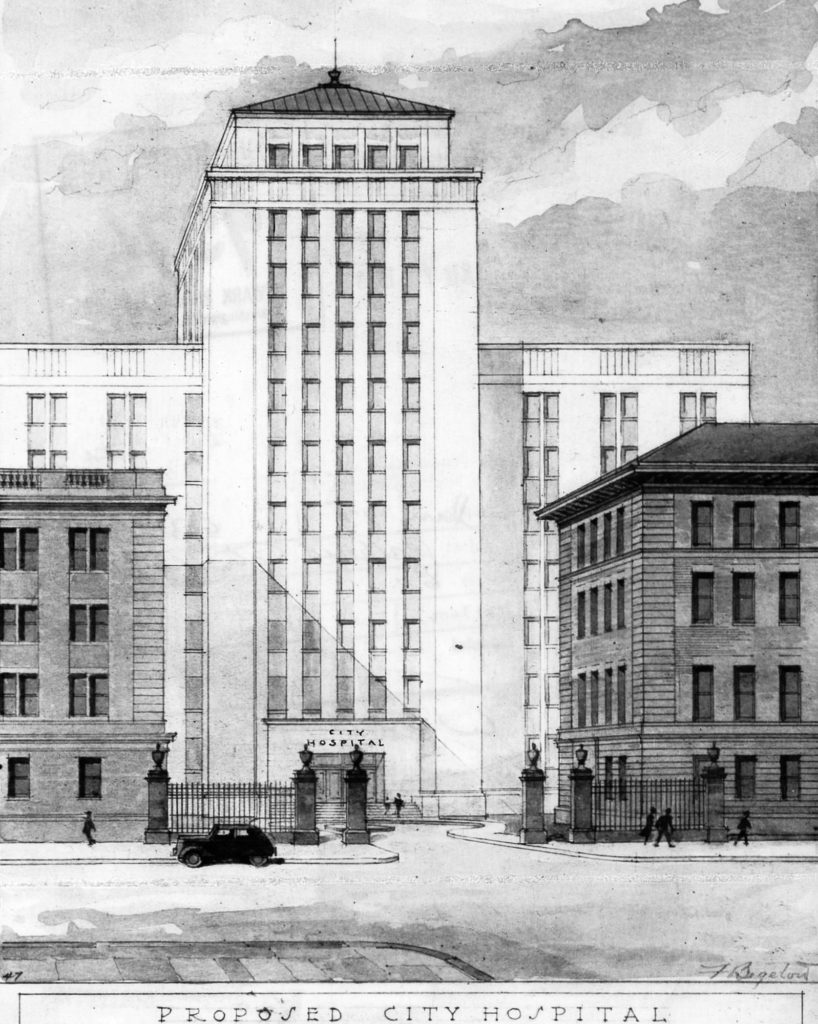

Months before, Newark mayor Hugh Addonizio had expressed his desire to have the school move to Newark. In late December 1965, when the governor-appointed board of trustees of the school voted to seek a firmer footing elsewhere in the state, Mayor Addonizio pounced. Newark, he said, would welcome the college “with open arms.” He declared his administration willing to arrange any program that would be acceptable to Governor Hughes and the trustees. City Hospital, its seventeen floors rising above the Central Ward, he suggested, could be expanded onto adjacent urban renewal land in order to create a “first class medical center to serve the state’s largest city.”

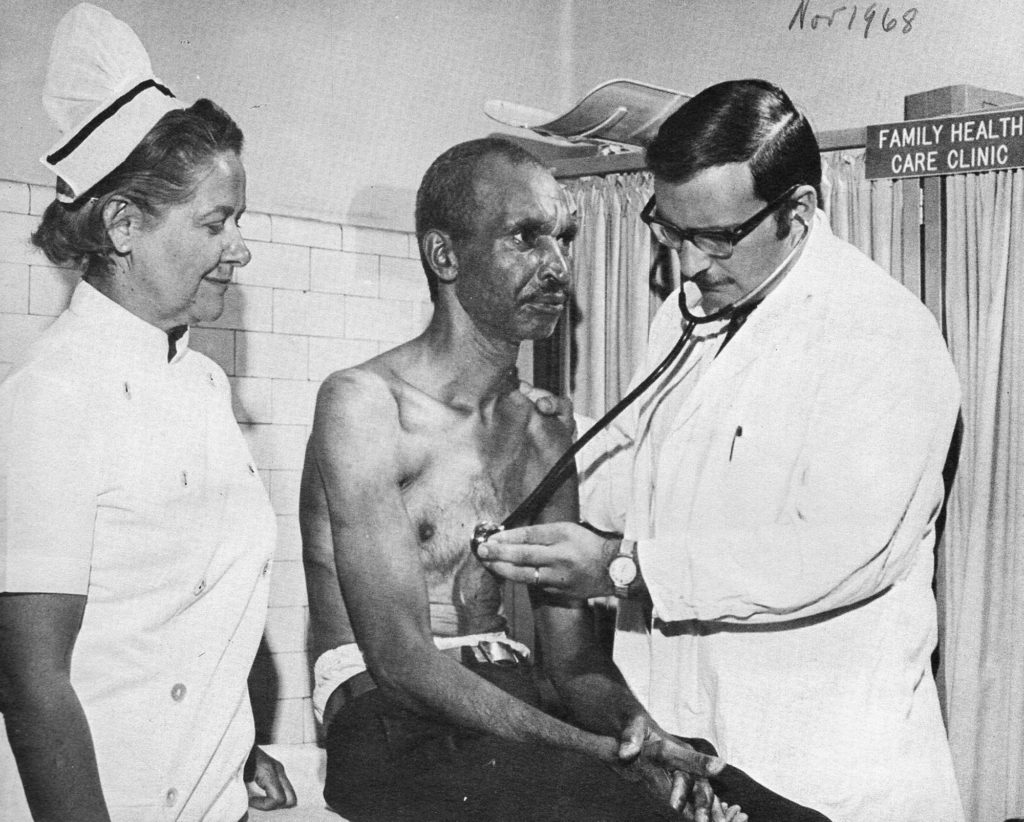

Newark, of course, had long ceased being the industrial powerhouse it was at the turn of the century. Manufacturing employment dropped precipitously in the 1950s, just as the double migration of the middle-class to the suburbs and black migrants to the city radically altered the city’s service needs. Newark’s 1964 “Master Plan” referred to this situation euphemistically, stripping it of its racial characteristics: “The continuing shift of population to the suburbs, the influx of new people into Newark, the rapid change in community composition have all brought additional demands on city health and medical facilities,” it read. A large medical school campus in the Central Ward would provide Newark an injection of middle-class, white-collar workers and provide services demanded by an increasingly black, increasingly less well-off population. Throughout 1966, therefore, the Addonizio administration heavily courted the medical school trustees. Municipal officials took them on tours of City Hospital and adjacent urban renewal land. They pointed out the city’s great need for the first-rate healthcare the school could provide and the wonderful training opportunities this opened for the school’s students.

Nonetheless, in August, the trustees’ site advisory committee recommended a more bucolic location in suburban Madison, fifteen miles west of Newark. Faced with the prospect of losing the medical school, the city made a desperate offer: it would provide over 150 acres in the heart of the Central Ward if the medical school decided to move to Newark instead.

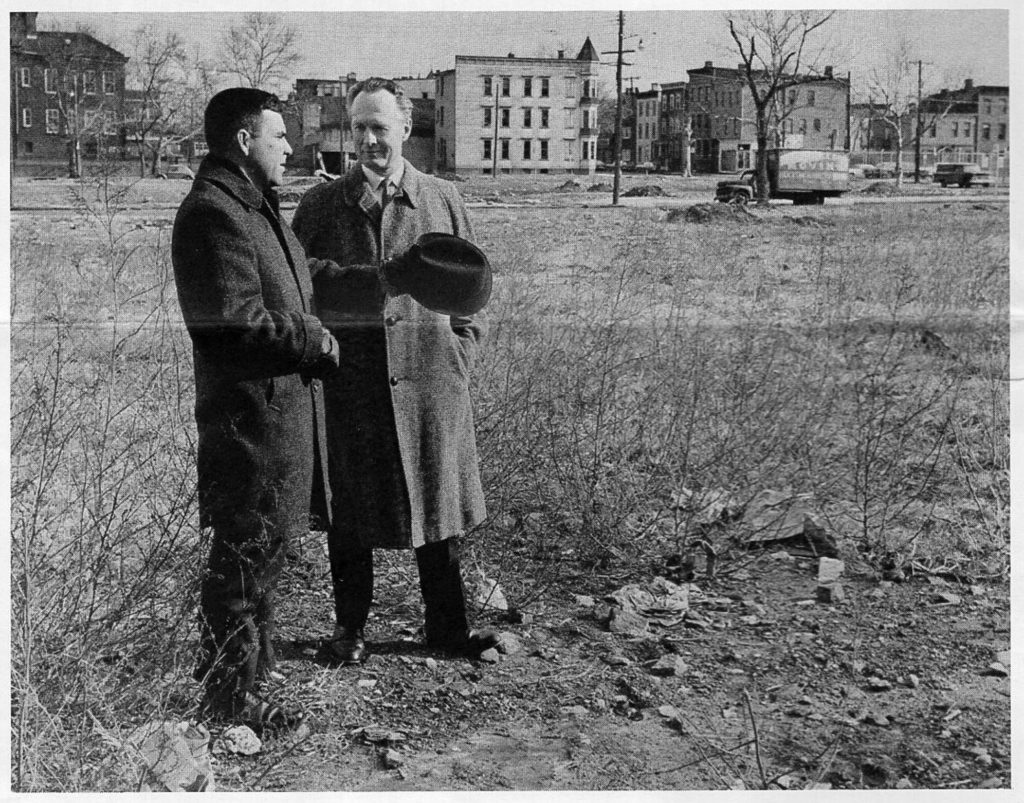

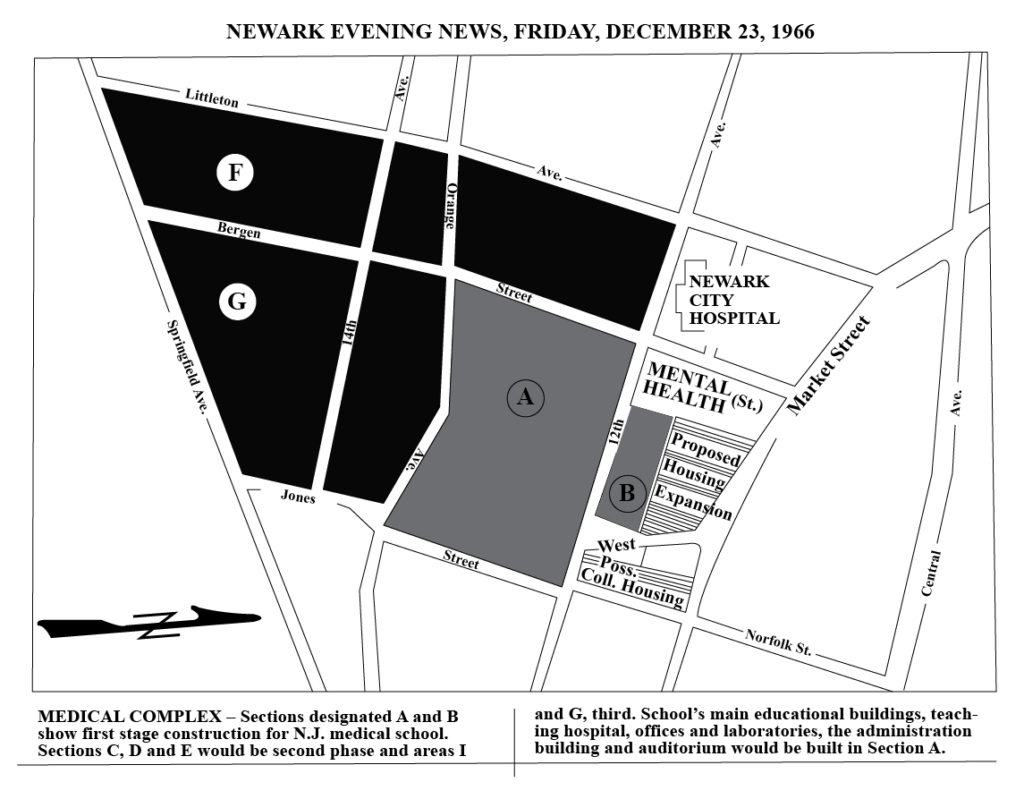

Addonizio and city housing director Louis Danzig guaranteed the trustees that, as Danzig put it, they could “deliver land on a continuing basis and in any quantity.” The heart of the city’s proposed offer was the Fairmount urban renewal area, already approved for federal funds and ready to go, which extended from South 7th Street to Norfolk and roughly from West Market to 12th Ave.

The promise of land – speedily acquired, cleared, and delivered – was the clincher, and in December 1966 the medical school trustees chose Newark as the school’s new home. But there was a catch: the promised urban renewal land, according to the trustees, was too irregularly subdivided to be of much use and would not make a practical campus center from which they could expand. Instead, for the first phase of campus construction, they demanded a tract southeast of City Hospital that, far from being empty urban renewal land, was a residential neighborhood of predominantly black renters and homeowners. “There’s no use trying to kid anybody. I’m disappointed and unhappy,” Mayor Addonizio said But his determination did not flag. “This is too important and I’m accepting this responsibility. I’m not going to let this get away from Newark.”

Fulfilling such promises had become the Newark Housing Authority’s expertise. A 1963 study sponsored by Columbia University and the Ford Foundation found that the NHA typically reversed the timeline followed by other urban renewal agencies: instead of locating a blighted area and then attracting developers to it, the NHA found it more expedient to locate the developers first and then decide on an appropriate site. With federal funds secured and anxious developers waiting in the wings, the NHA had no trouble securing a blight declaration for the targeted land from the Newark Central Planning Board or the approval of the mayor and city council. The study found that it was “self-evident to Authority officials that the formative stages of a project must be protected from excessive public interference” and it praised the resulting efficiency of its projects.

As one anonymous NHA official put it, the authority “own[s] the slums. They can sell any piece of real estate in that area to a redeveloper before it’s even acquired. And they don’t have to check with anyone before they do it.”