Intersections Part 1

by Adrienne Wheeler

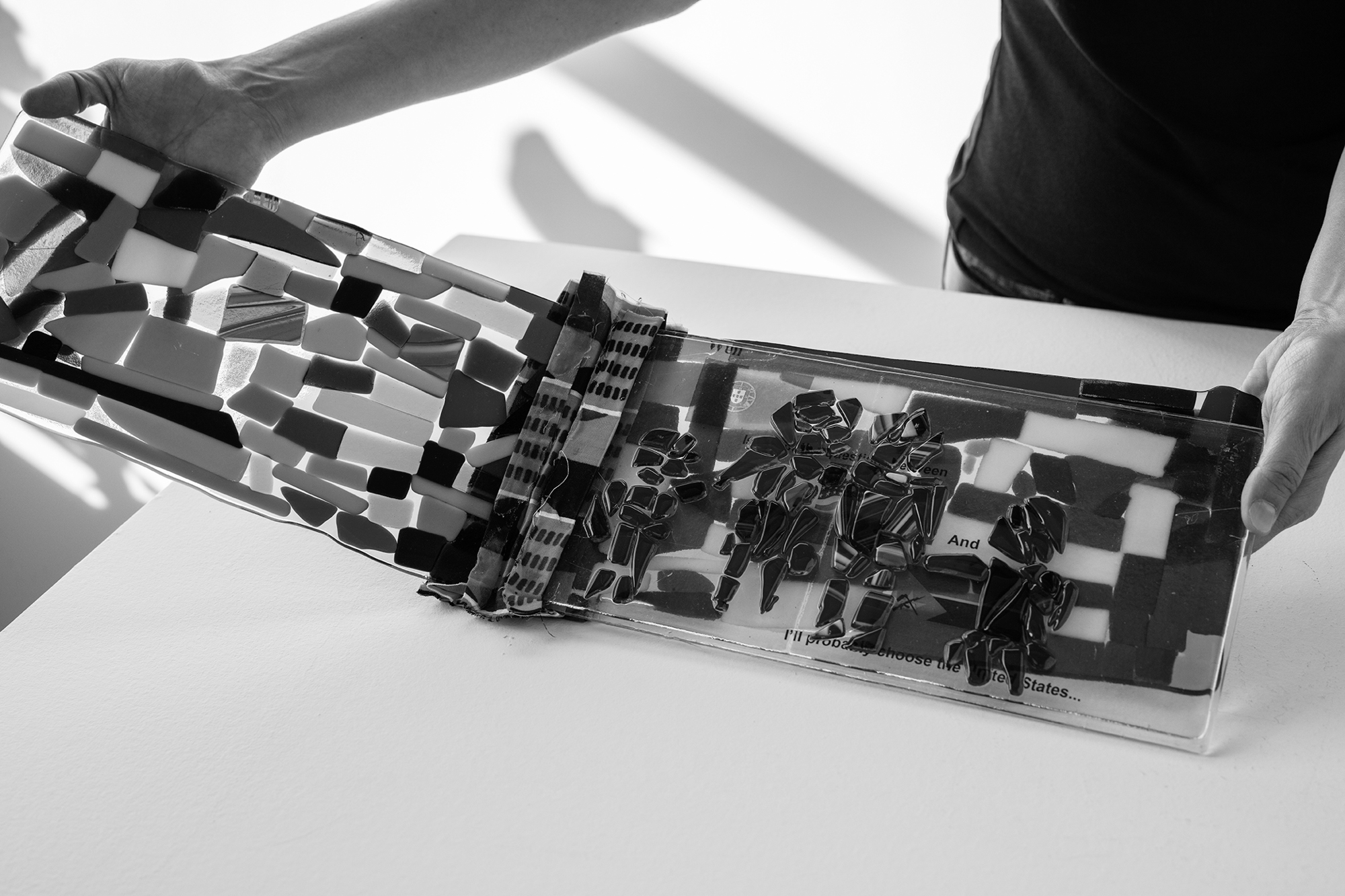

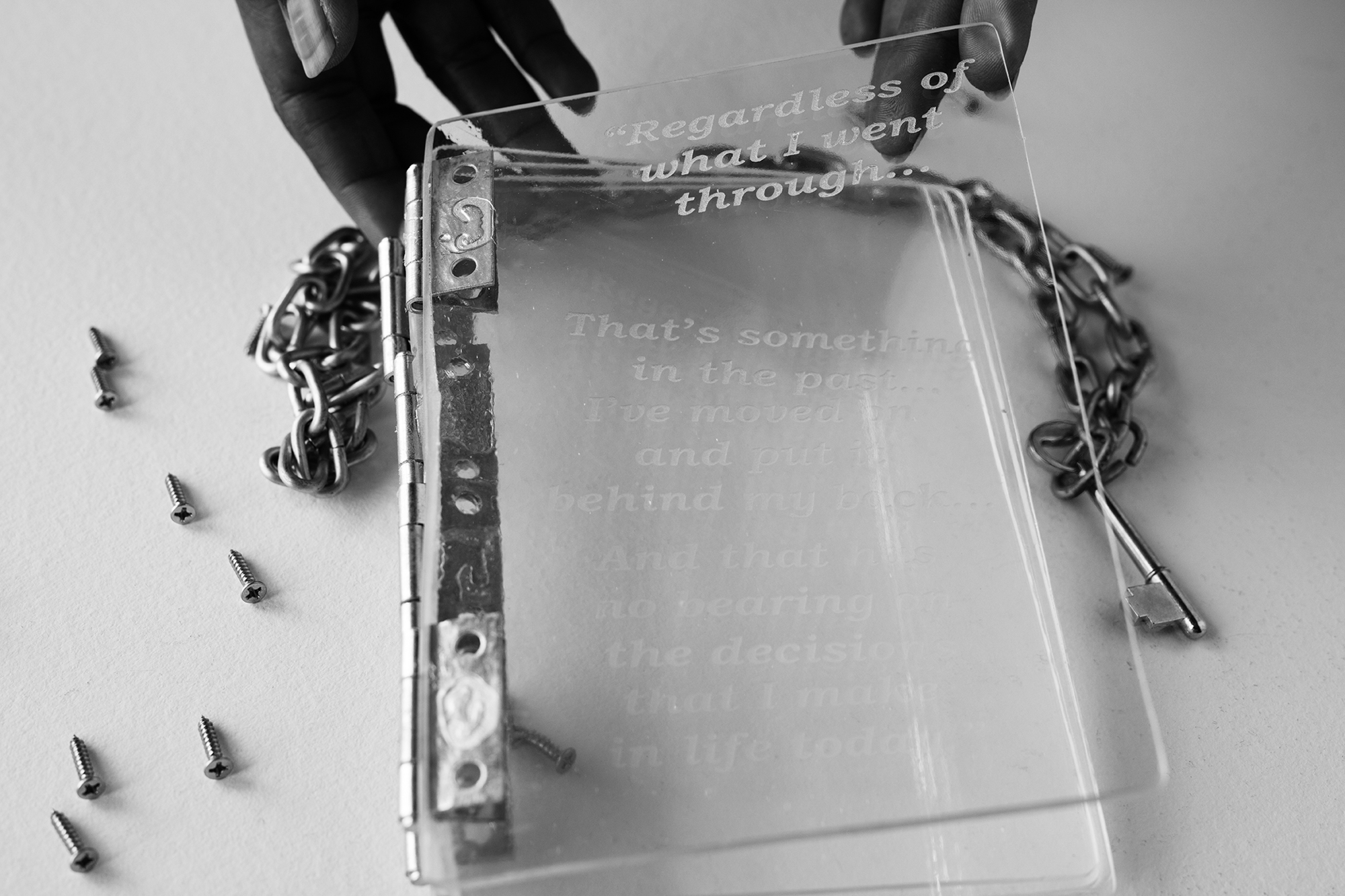

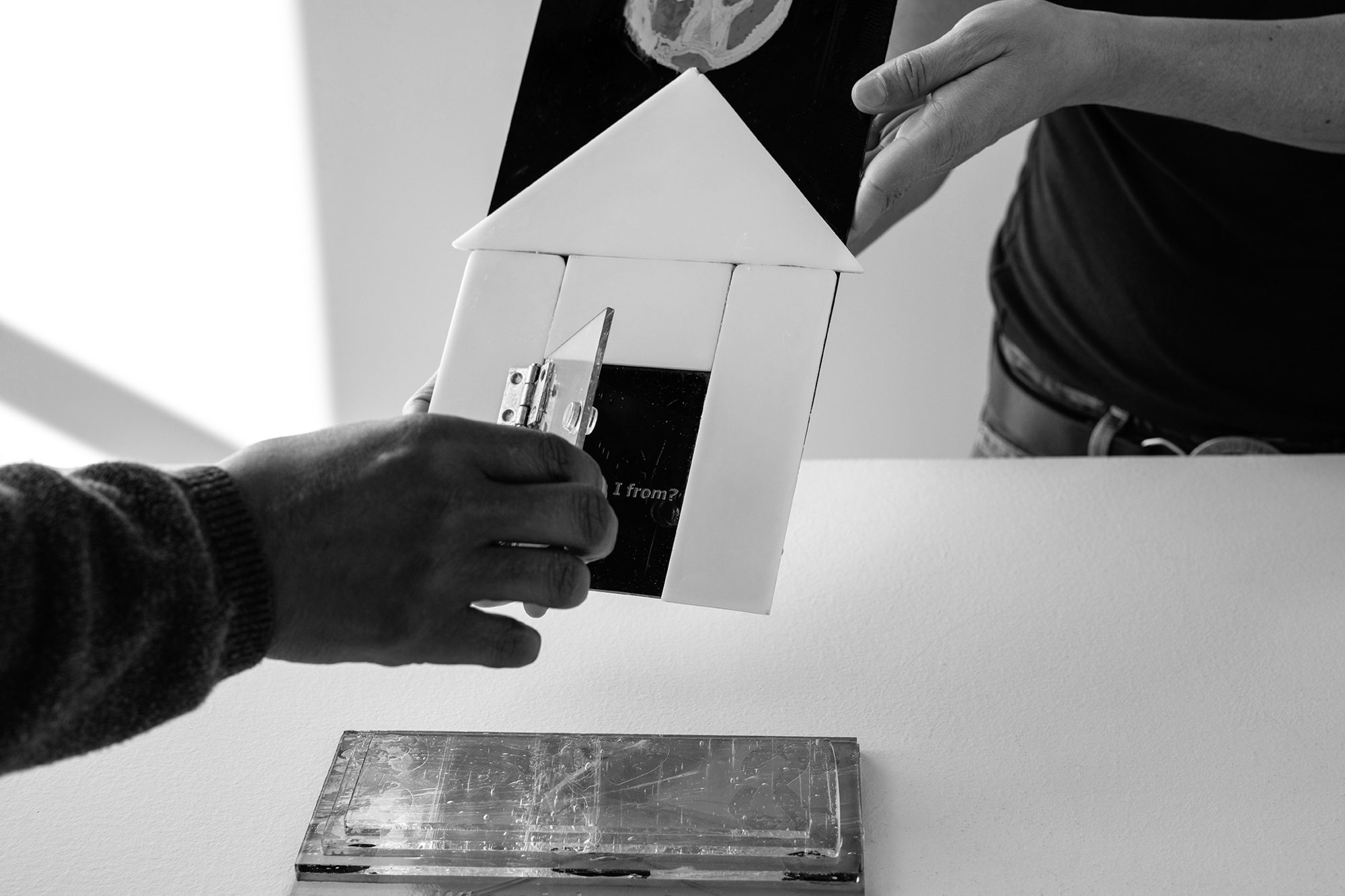

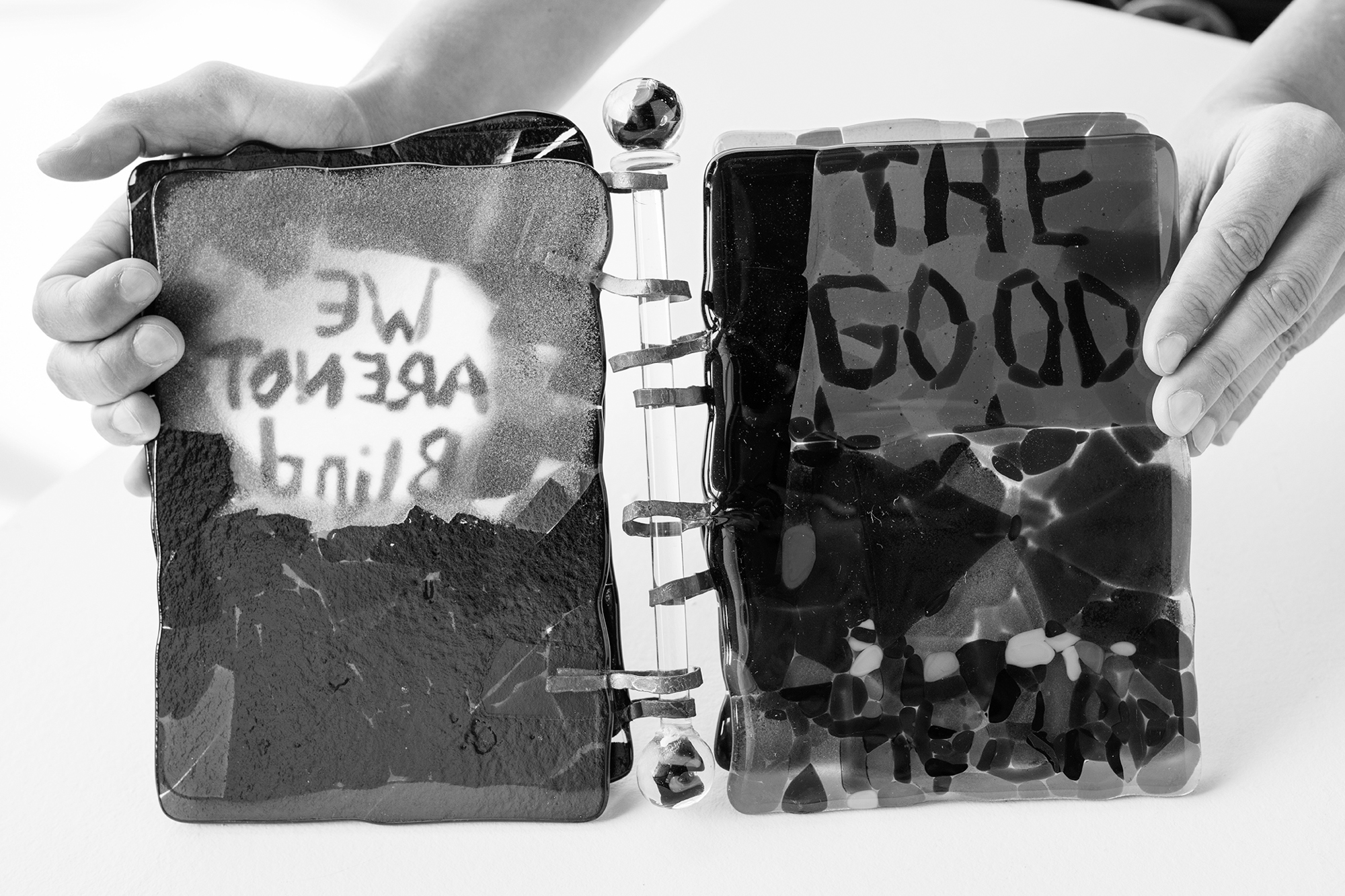

Brick by Brick was a collaboration between myself, writer/poet paulA Neves, Dr. Tim Raphael and students from the Honors Living and Learning Community (HLLC) at Rutgers University-Newark in a course we taught in the spring of 2017. Our work was part of the GlassBook Project, a socially-engaged artwork founded by artist Nick Kline. The class and the glass books we created were inspired by interviews from the Ironbound Oral History Archive, a collection of over 250 interviews with Lusophone migrants to Newark that have been conducted since 2002 by Dr. Kimberly DaCosta Holton, director of the Portuguese and Lusophone World Studies program at Rutgers University-Newark, and her students.

Listen to the latest Newest Americans podcast about “Brick by Brick.”

Brick by Brick: The Podcast

In one of the first classes we began talking about the various identities we inhabit; individual, familial, cultural and national. One student remarked that he identified more with his dad who is African than with his mother who is “just African-American.” I was stunned, and wondered how he perceives me and an entire community of people, he defines as only, merely, simply, nothing but, no more than African-American. His perception conflicted greatly with how I had been raise to see myself and my community as exactly, precisely, absolutely, completely, totally, entirely, perfectly, utterly, wholly, thoroughly, in all respects African-American.

Emmanuel Marvilus

This became a pivotal moment for me in guiding the students (many of whom were either immigrants themselves or the first generation born outside of their family’s country of origin) through the process of interpreting other’s stories while maintaining the integrity of each. Their moments of discovery took paulA and I back to a conversation we had when we first met, during the creation of the collection called Provisions, inspired by interviews with African-American residents of Newark, NJ who migrated to the city between 1910 and 1970. This was my mother’s story. My conversation with paulA had been about the strained relationship that has existed historically between the Portuguese and African-American communities in Newark. This relationship is complex and rooted in identities shaped by histories of colonization and slavery.

Yeimy Gamez Castillo

In Newark’s Ironbound, Portuguese immigrants, many of whom had fled the dictatorships of a colonial empire, encountered the descendants of formerly enslaved Africans and African-Americans whose identities are tied to related histories. While not from a Lusophone community, my paternal, Wheeler family history in the Ironbound–or what we still refer to as “Down Neck”–dates back to the nineteenth century. The African-American presence in the Ironbound before the twentieth century is not well documented, and requires accounts from other migrant communities to piece it together. So paulA and I kept talking.

Gracie Appiah

Somewhere along the line we realized that the place where our family histories intersected was Tony da Caneca’s restaurant, way Down Neck, the first restaurant of its kind to open in the Ironbound, and frequented by my family in the 1960s because the food was great and we were welcomed there, which wasn’t the case for blacks in many of the other Portuguese restaurants in the area. One block from the restaurant is Wheeler Point Road. According to my father, the street bears our name because the property it defined was owned by my family some time between 1840 and 1900.

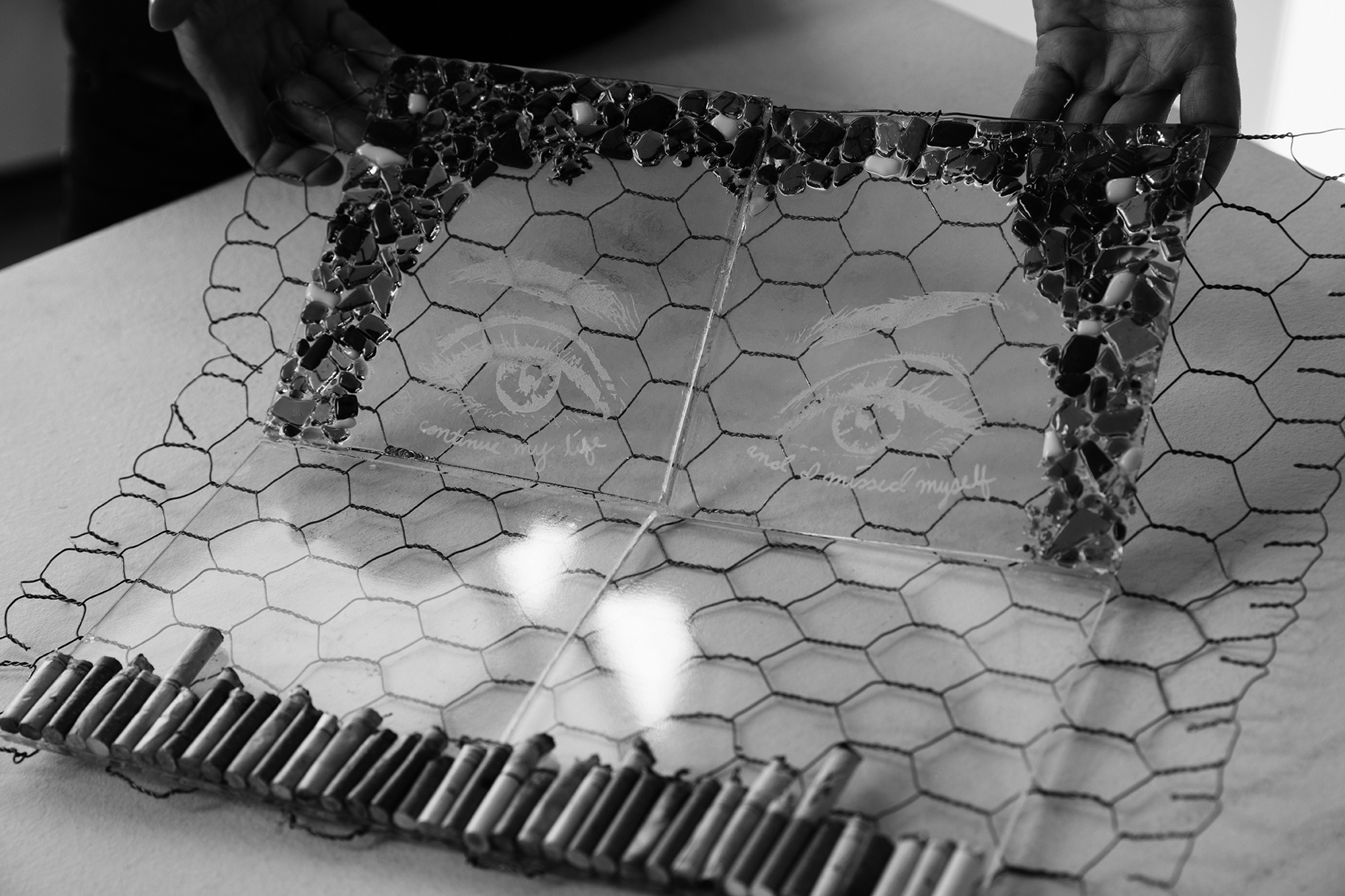

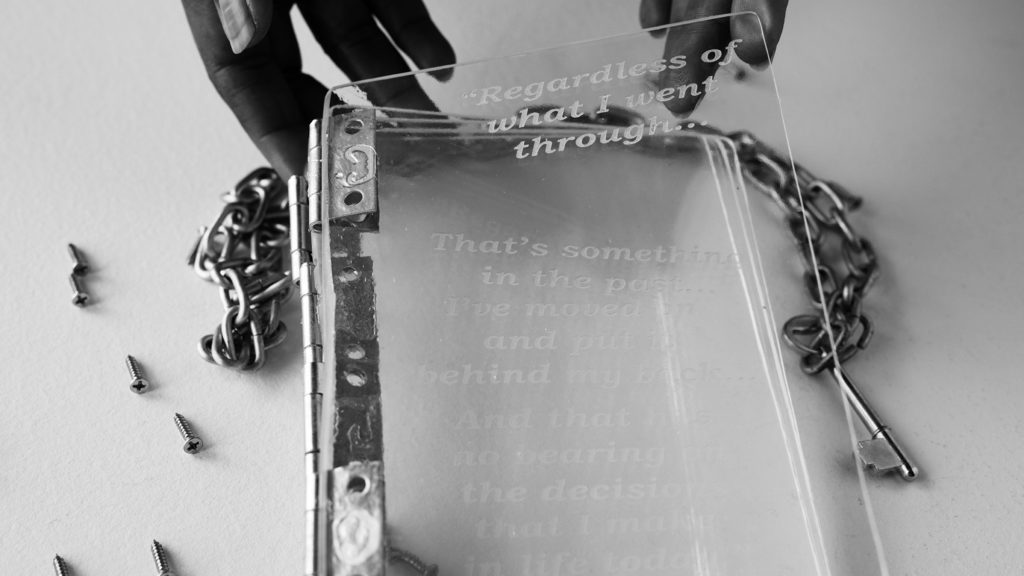

As the semester progressed something magical began to happen – the students became fully engaged and excited about the work they were doing. They realized that their contribution to the project would be significant. One student, who had earlier considered dropping the class, “dug deep” and produced a compelling docu-narrative and glass book, not a sculpture but an installation with more details and components than we had seen in previous collections. Another student, who identified with one of the interviewees who had been abused by a priest in the Catholic Church, found another place for healing through the making of his glass book.

Sabrina Ahmed

As part of the Honors Living and Learning Community, these students came to us already a community unto themselves with a highly developed sensitivity to each other’s stories. They all listened to and/or read each of the 16 interviews we gave them before selecting one interview, one life story to inspire their abstract portrait. As a result, they encountered stories that mirrored their own, and some that were entirely unfamiliar. This, along with creating their own docu-narratives, gave them the opportunity to walk in someone else’s shoes and not feel isolated in their own stories.

As for the impact on paulA and I? We continue to collaborate on telling our families’ interconnected stories and placing them within the larger contexts of Down Neck, Ironbound and American histories.

“Many stories matter. Stories have been used to dispossess and to malign. But stories can also be used to empower, and to humanize. Stories can break the dignity of a people. But stories can also repair that broken dignity.”

― Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

Aldo Villarreral

Intersections Part 2

This Isn’t Angola or Mozambique (O Preto)

– after Carrie Mae Weems’

by paulA neves

I Looked and Looked to See What So Terrified You

I looked and looked to see what would work.

I laughed in the vanity, eyes lined with kohl.

Caveira I was with night years for eyes, you at 2

could not tell mother from skull on the cover of the Times —

Lord, at 19, with you, I felt as old as that Lucy

delivered by the mailman who, luckily, was black,

perfect timing because you wouldn’t eat your soup.

O Preto will get you! O Preto!” “No, I eat, I eat!”—

as I collected the mail for the Americans upstairs.

You never saw him on the stoop, but thank God you knew

just from his being that you’d better believe.

My bruxa eyes made you clean only half of your bowl.

Try me again. No child of mine will make others accuse

me of neglect. This isn’t Angola or Mozambique.

– paulA neves

The poem emerged from a memory of my early childhood in the Ironbound. Memories, like dreams, are unreliable narrators but obey their essential truths. And my truth was an early awareness that even though Ironbound was a place in a city called Newark, the Newark I was growing up in was many cities. The city in Newark my mainland Portuguese immigrant parents had chosen in the 1960s, and where I, and later my brother, were born, was one filled with people who looked like us, shared similar stories of life back “home” and commiserated over similar struggles of trying to land jobs, raise children with the language and traditions of o nosso povo (our people).

Thamivili Sivanesan

Our little city was bounded by factories and highways, and especially McCarter Highway, that artery we never crossed unless it was to go shopping downtown on Broad Street, when the offerings of the mom and pop shops on Ferry St. didn’t suffice.

And that’s when we saw those from the other city in Newark. These were the people we never saw in our city unless they came to deliver mail or rumble down Delancy in trucks carrying goods from Port Newark. There was an unspoken understanding that when our paths crossed, though we would treat each other civilly, we were still residents of different places.

Justin Wiggins

But at the end of my street in the Ironbound, there was a bar/restaurant, Tony da Caneca. The place was across the street from Mrs. Francisca’s house, the woman who watched us while my mother worked at a light factory on Chestnut and my father unloaded containers at the Port. Standing behind Mrs. F’s front gate at in the afternoon after school, I watched men like my father enter after work and leave just before dinner. Some of those men had fought in Angola and Mozambique during the colonial wars. Those conversations were never part of the standard reminiscences. But their shadows hung over many families. I watched the traffic in and out of Tony D’s to find out what the allure was. And then my mother would usually appear.

Tanaisa Brown

I don’t recall my family ever having a meal at Tony D’s. Maybe we did for a baptism or a festa. More likely we didn’t. It cost money to eat at a restaurant, and why should we spend money on the exact same food we got at home, and made better too.

But a family that did frequent Tony D’s during that time were the Wheelers. And this I didn’t find out until the spring of 2015, long after my family had left the Ironbound, but just mere months after I’d had my mother’s funeral repast at Tony D’s.

Hansier Rodriguez

“Yeah, our family used to eat there,” Adrienne recounted. She was one of the teaching artists for the GlassBook Project’s “Provisions” class at Rutgers University-Newark inspired by the life stories in the Krueger-Scott African American Oral History Archive. I was taking the class and teaching a guest seminar on writing artists statements. Adrienne and I immediately connected. “We were always treated respectfully at Tony’s,” she told me.

I was dumbfounded. The two Newarks I’d known as a child had indeed intersected, and I hadn’t known it. It was a powerful moment for me.

Andrew Vazquez

Exactly two years later, in the spring of 2017, I unexpectedly (but delightfully) found myself being one of the teaching-artists for the next iteration of the project. Appropriately enough it was “Brick by Brick: The Ironbound Oral History Archives.” Adrienne Wheeler was another of the teaching artists. We exchanged some version of “Why am I not surprised?” The Rutgers-Newark community is small in many ways, but this was not what this ongoing kismet was about.

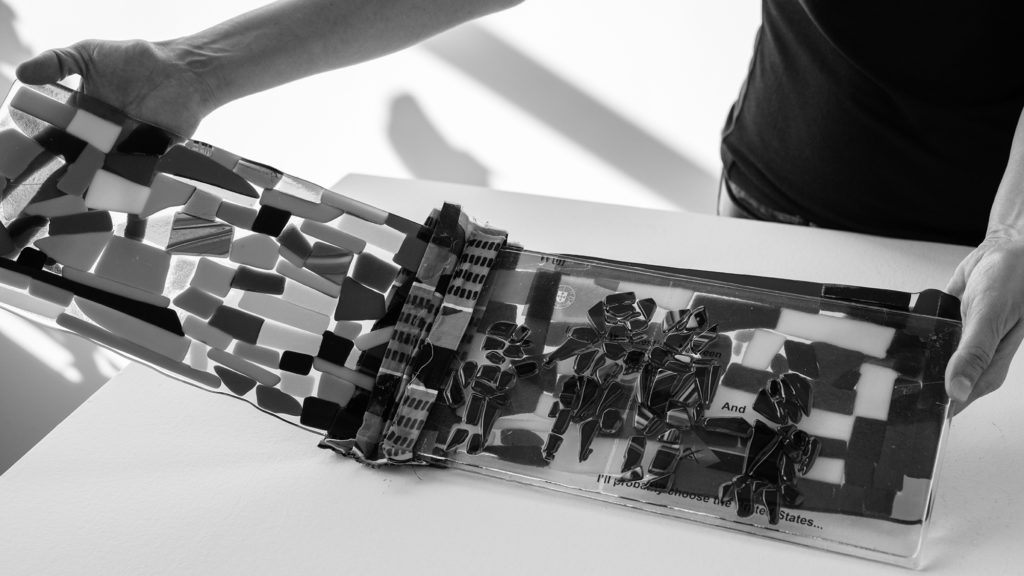

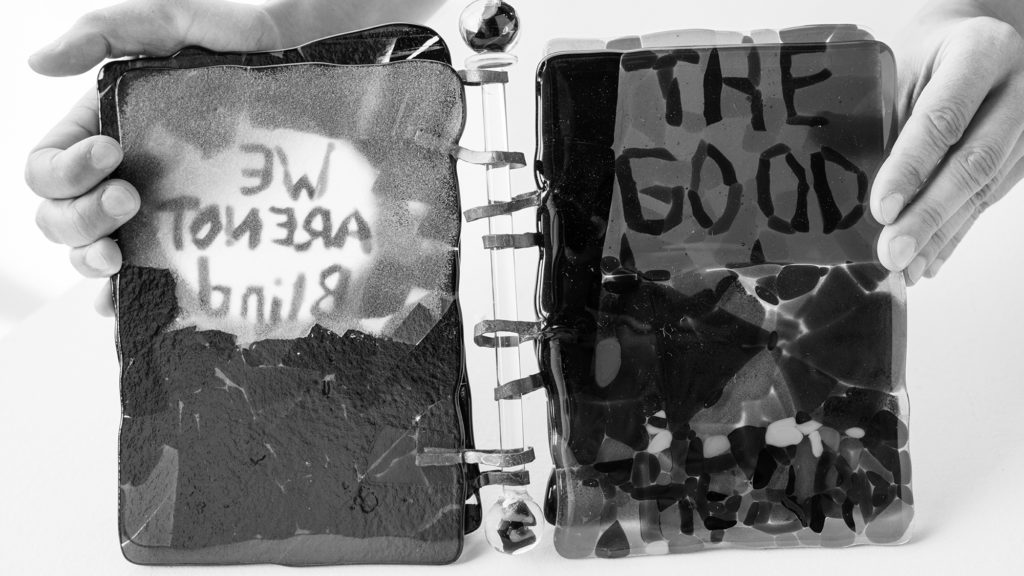

And the book sculptures we created speak to this. Adrienne’s Lamentations/Lamentações, an abstraction of railroad tracks, considers a history of colonialism and overt or subtle racism through “a representation of a neighborhood bound by the railroad, and metaphorically the ways in which we remain bound to ideas and attitudes.” My And We Became These American Girls evokes film negatives of a life built on traditional attitudes that are challenged by a place like Newark, where “[t]hose American dreams unspool into lives of greater choices—to cross the tracks, leave the neighborhood.”

Jeffrey Fuentes

Many of our students’ works, some of which are presented here, also suggest the same awareness of the dance between division and intersection.

Adrienne and I are now developing a collaborative project about our two cities in Newark. We discuss it often over dinner and drinks at Tony da Caneca.

―paulA Neves