Fado: A Transatlantic Story

In Portugal people know about Newark. Articles about Newark’s “Little Portugal,” otherwise known as the “Ironbound,” grace the human interest sections of Portuguese newspapers; photos of Ironbound bakeries, parades and urban gardens show up in the Facebook feeds of Portuguese folks with friends and family living in New Jersey; in the days of The Sopranos, Newark’s Sheriff Armando Fontoura, a Portuguese-born fighter of American crime, landed on glossy covers of Portuguese magazines, queried as to whether filming the popular series in Newark was good for the city’s image. But, aside from TV gangsters and far-flung countrymen, perhaps the most salient feature of Newark’s identity in Portugal is its reputation as the US “Catedral do Fado” (or “Fado Cathedral”).

What makes Newark a Fado Cathedral? And is the lofty moniker a fair description of the Portuguese music scene here in Brick City? While Providence and Toronto might balk at the designation, Newark does indeed have a uniquely vibrant and varied fado scene—one which involves vocalists, instrumentalists, composers, lyricists and concert producers, and which draws crowds of both insiders and outsiders to performance venues throughout Newark’s East Ward. And although its history on U.S. soil is not as long as its presence in Iberia, fado, the urban ballad form sometimes

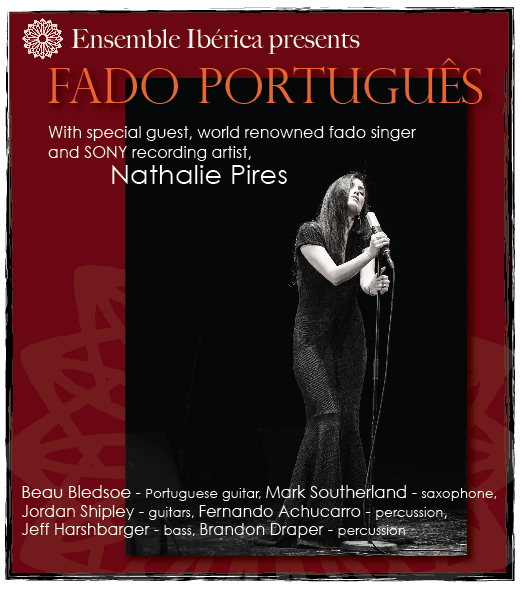

called Portugal’s “national song,” has been firmly entrenched in Newark since the mid-twentieth century. Newark has also recently begun exporting musical talent back to the motherland. New Jersey fadista Nathalie Pires—subject of the Newest-Americans short film Echoes of Fado—has just returned from a series of concerts and recording sessions in Portugal. Her soulful and skilled renditions of fado classics, learned in her childhood home in Perth Amboy and debuted in the restaurants and clubs of the Ironbound, highlights fado’s trajectory as a transatlantic, two-way story of influence and cross-pollination.

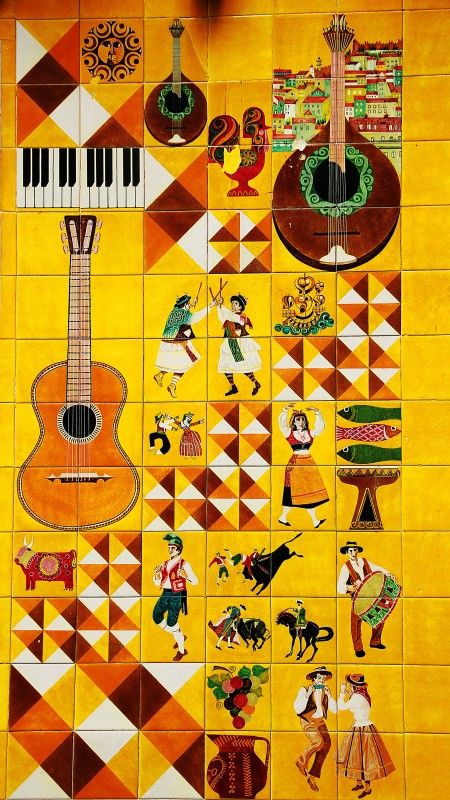

Fado, best known as a melancholy music sung by a solo vocalist dressed in black, accompanied by two guitars—a six-string acoustic guitar and a 12-string guitarra portuguesa—boasts a colorful history comprised of many chapters. The mournful ballad form first appeared in the rough and tumble riverside neighborhoods of 1820s Lisbon. Fado was initially associated with the underbelly of urban life; prostitutes, sailors, vagabonds and drifters who would gather on the streets and in gritty taverns were among fado’s first performers—drinking and smoking, singing and strumming. Fado’s early incantation featured vocal and lyrical improvisation and verses about the difficulties and curiosities of daily life. Musically, fado’s influences stem from a variety of sources. Scholars debate which influences dominate—the Afro-Brazilian influence passed down from portside denizens of late 18th century Rio de Janeiro who danced something called “fado” alongside other related genres hailing from Africa such as the lundum and fofa; Moorish or Mediterranean influences sometimes heard in fado’s vocal “runs” or guitarra solos; the European troubadour influence glimpsed in the features of some fado story-songs and in fado’s traditional instrumentation. Just to name a few.

Fado’s vast melting pot of musical ingredients and influences continued to percolate and blend over time. Several decades after its riverside birth, fado moved indoors and into more rarified confines. Dark taverns gave way to salons and drawing rooms, as Portugal’s upper classes adopted fado. The portable guitar was joined by the piano, as fado’s oral tradition of rote learning and on-the-fly composition gave way to more fixed lyrics and melodies transcribed onto sheet music, and later, even symphonic and operatic arrangement. In addition to its entry into the middle and upper classes, fado also mixed with popular rural traditions transported back and forth between city and countryside by beggars and blind musicians.

In the twentieth century, the recording industry furthered fado’s aesthetic fixing, and made the music available to an international audience. Fado’s popularity grew as it entered the world of radio, theater, television and cinema. At the same time, however, the strict censors of the Estado Novo regime (1926-74) clamped down on fado lyrics, taking red pens to lyric sheets, rejecting what they deemed to be “subversive” content. Curiously, at the same time the censors were reducing the breadth of fado’s lyrical subject matter, Portuguese poets turned their literary attentions toward fado, writing poems for a growing class of fado divas. Thus, a lyrical impoverishment and a lyrical enrichment occurred around the same time. During the 1950s and 60s, sometimes called fado’s “Golden Age,” literary heavyweights such as Pedro Homem de Melo, David Mourão-Ferreira, and José Régio among others authored poems that remain core to fado repertoire today. The great diva, Amália Rodrigues, put many of these fado poems into wide circulation; her unparalleled voice and inspired interpretations contributed greatly to the enduring popularity of many of the fado poems of this period.

So how has fado’s trajectory, with all of its fitful twists and turns, arrived at the present moment? Well, almost two centuries after its first appearance in Lisbon, fado has continued its protean evolution by entering a new phase. You might even say fado has hit a high water mark as of late. Awarded World’s Intangible Cultural Heritage status by UNESCO in 2011, fado has attracted a new generation of singers and guitarists who are headlining marquee stages around the globe. A growing cadre of scholars have published books and dissertations on the urban ballad form. Historic recordings of Amália Rodrigues and other 20th century greats have been rereleased, while fado tracks, old and new, are being consumed and shared online among an ever-growing fan base. The singular Museu do Fado, a Lisbon treasure trove of primary documents, recordings, exhibitions, and educational programs, has opened its doors to a hungry public. Portuguese university programs have been created for the teaching of fado voice and guitar—pedagogy which, until very recently, had only taken place informally, outside of institutions of higher learning.

Immigrant outposts of fado performance overseas have also strengthened and grown. In Newark’s Ironbound neighborhood the fado scene has survived without interruption for at least 5 decades. And in the last several years, thanks to creative motors such as Proverbo, the cultural arm of the Sport Clube Portugues, the Tertúlia do Fado, a group dedicated to teaching, performing and discussing fado, and the Amália Foundation USA, an organization charged with preserving the memory of fado diva Amália Rodrigues, the fado scene in NJ/NY has experienced an infusion of new ideas and energy, while growing new performers, publics, lyrics and performance traditions.

The Ironbound has seen fado performance venues come and go over the years. But as soon as one venue closes its doors to fado, another seems to open up. At one point there were even two dedicated Ironbound casas do fado (“fado houses”—the spaces in Portugal where fado is performed regularly, sometimes nightly, and where a system of informal apprenticeship nurtures a new generation of singers and instrumentalists). At the moment, fado is performed semi-regularly in one Newark restaurant. It is also frequently performed in Portuguese-American social clubs such as the Sport Clube Portugues and the Casa do Ribatejo. There are annual galas in Northern, New Jersey that feature fado—the Portuguese War Veterans Gala, the Proverbo Gala, the Amália Foundation Gala, The Annual Concurso do Fado (“Fado Contest”) and the Annual Noite do Fado (“Fado Night”). Fado performances and exhibits are also an integral part of the Newark Portugal Day festivities in June every year. Taken together, there is rarely a month that passes without at least 2-3 opportunities to hear fado performed live in Northern New Jersey.

The reason the New Jersey fado scene continues to expand and export performers like Nathalie Pires is due to the diverse and growing group of people who sing and play this ballad form locally. Being able to sing fado—with all the emotional intensity required—is often thought of as something you are born with. And indeed, many local performers have family members who are musicians or fado aficionados, and therefore have fado “in their blood.” But others have learned fado “cold”–through purposeful study and practice in a satellite location far from the music’s originary source and support structure. Many have relied on Internet recordings in order to understand fado repertoire and to begin learning how to sing fado by emulating past performances of fado greats. Recently however, self-study has been complemented by evolving support systems for nurturing young fado talent. Fado instrumentalist José Luis Iglesias and vocalist Fátima Santos, for example, founded “Tertúlia do Fado”—an association of fado performers and aficionados who meet weekly, offering lessons, workshops and opportunities for organizing performances.

Over the years veteran fadistas such as Elizabeth Maria, Fatima Santos, Corina, and Emilia Silva have developed their own careers while taking younger singers under their wings. Local poets such as João Martins, Glória de Melo, Anabela Martins, and Luis Lourenço have written new fado lyrics, some adapted and performed by NJ fadistas seeking to diversify their repertoire. Instrumentalists including the late Alberto Resendes, Francisco Chuva, José Luís Iglesias, Tony Cirne, and Michael da Silva, have offered advice, support and practice sessions for the up and coming singers. Younger singers, now in their twenties, such as Nathalie Pires, Pedro Botas, Kimberly Gomes, and Davide Couto have benefited from the local support network and developed their own public following. And now in turn, this successfully launched twenty-something generation is mentoring an even greener crop of fado singers—some as young as 9 or 10 years old.

Coming full circle, it is important to acknowledge fado’s multi-directional trafficking across continents and oceans and within varied spheres of cultural influence and adherence. New Jersey fado performers hail from many different regions in Portugal, including the Azores Islands. Some are foreign born and Portuguese-language dominant; others are second generation and bilingual; others are third generation and English-language dominant. What they all have in common is a love of fado—a music characterized by its emotional range, sometimes jocular and upbeat, but more often heavy and sad with lyrics lamenting the absence of beloved places or people. NJ guitarist Franscico Chuva once told me, “Who better to understand what fado is all about than immigrants. We are the ones who experience loss and longing everyday. Being away from home. If anyone is suited to perform fado well, it is us. Immigrants who understand from experience what fado lyrics say about longing for things that are not here.”

What strange power does this melancholy song form possess that explains fado’s broad and enduring appeal across many different time periods and many different locations? It is perhaps the moment of the vocal peak where fado’s enchanting power is most tangible. The voice and the twelve-string guitarra share the melody, alternating passages. The climax of the song is often telegraphed by the singer’s gestures. She will bend her head back and sometimes close her eyes, the fringe of the traditional black shawl held tight in clenched fists. And towards the end of the fado, into the silence created as the guitars drop out, the fadista’s voice rephrases a melodic hook, improvising a near weeping along the notes, a musical surprise, as her voice continues pushing and retreating, catching the listener off guard, until the melisma reaches its dizzying climax. After a hushed moment, the guitars break their silence and come back in, and the audience realizes they’ve been present for something beyond the expectations of the everyday.