Newark Mayor Ras Baraka talks about Zanzibar

Despite sitting in the shadows of New York City, Newark has always been an incubator for its own musical sound.

As befits a city founded in 1666, Newark was home to some of the first American composers, including minister James Lyon, who published the first song and music book in the colonies. In 1920, another musical lion, Willie “The Lion” Smith, became the first African American recording artist when he played piano on the first blues record, “Crazy Blues” by Mamie Smith’s Jazz Hounds.

Since those early innovators, the city has seen its fair share of breakout artists– from Wayne Shorter to Queen Latifah, Jerome Kern to Whitney Houston, Sarah Vaughan to Ice-T – and a thriving nightlife that has spanned multiple decades and musical genres. Today, a multicultural underground scene reflects the energy of musicians like Guyanese-American Chris Bacchus and his band, Sunny Gang, featured in the film above, who draw on hip hop, ska, reggae, and rock to make their own brand of punk.

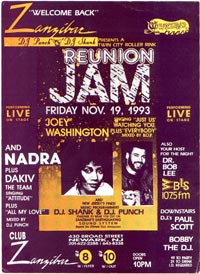

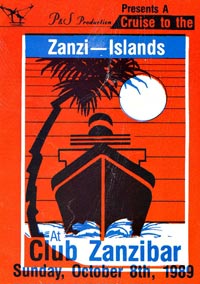

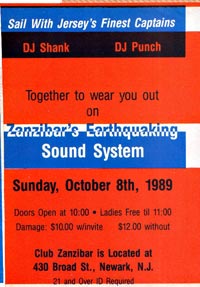

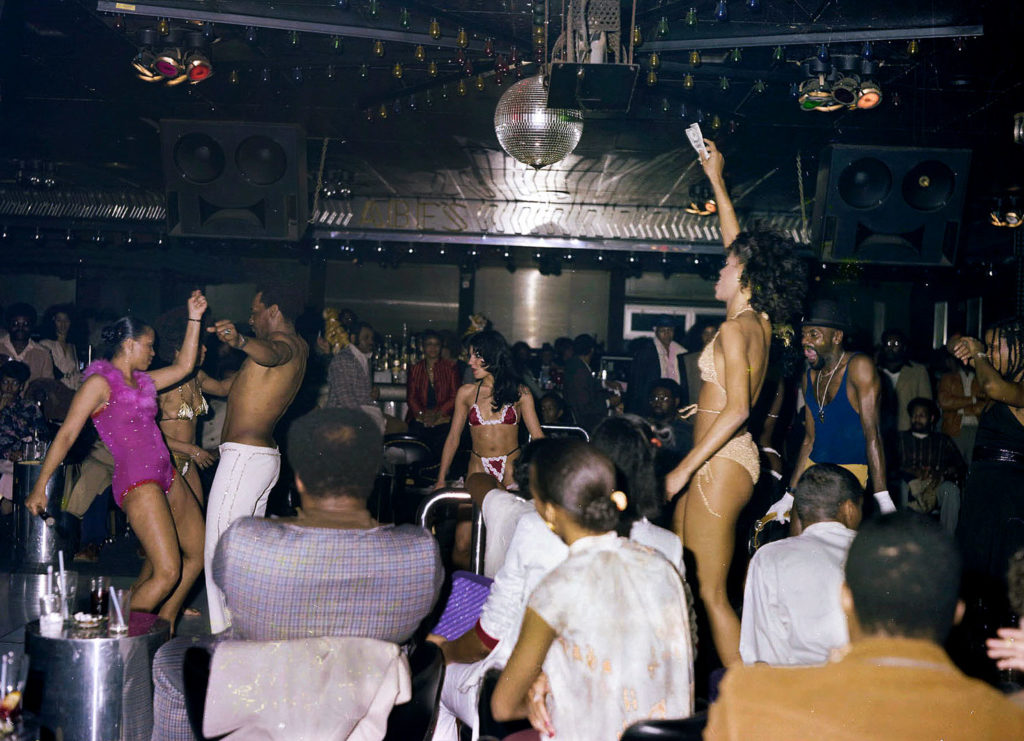

In the 1980s, another Newark music scene emerged from Club Zanzibar, a vibrant, eccentric nightclub where literally anything was possible. Trendsetting DJs and icons like Chaka Khan, Grace Jones and Patti Labelle mingled with caged tigers, leopard-clad dancers and an eclectic mix of gay, straight, black and brown patrons to make Zanzibar THE place to be.

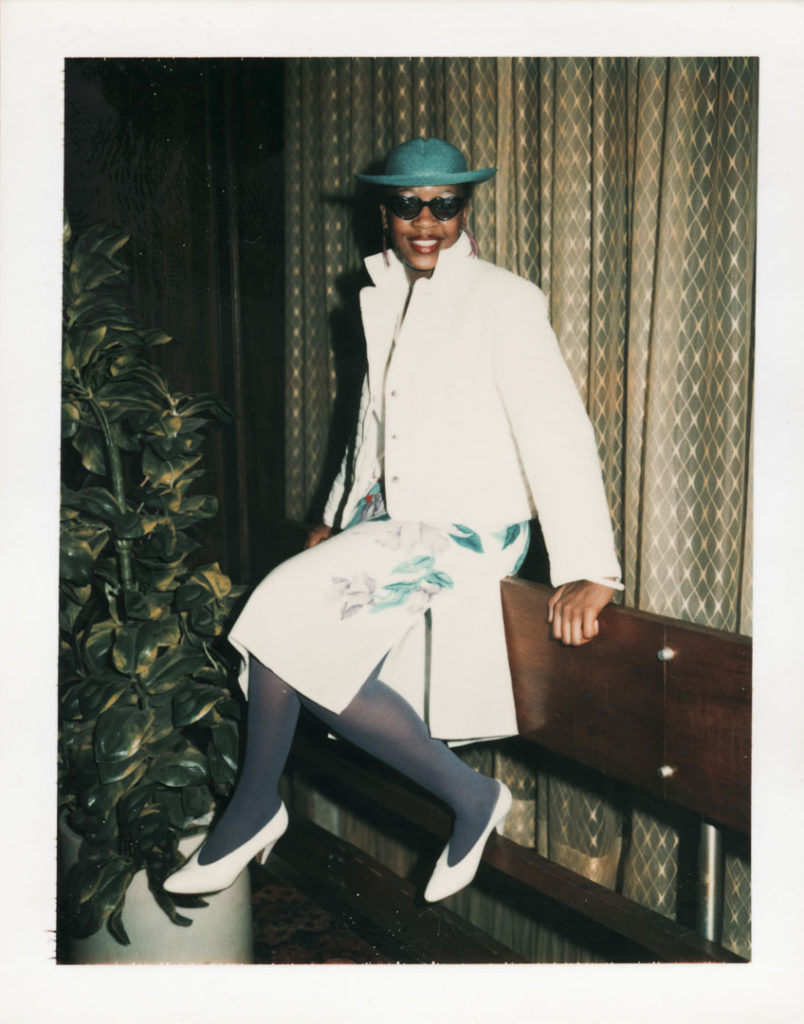

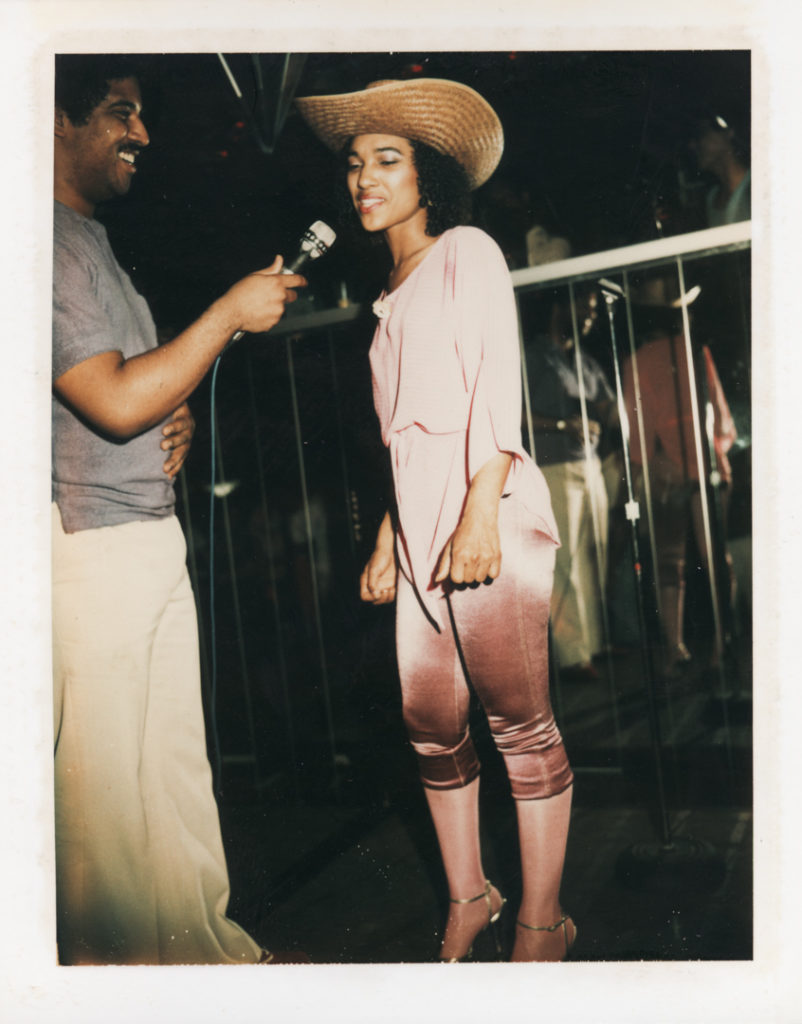

Grace Jones (center) at Zanzibar.

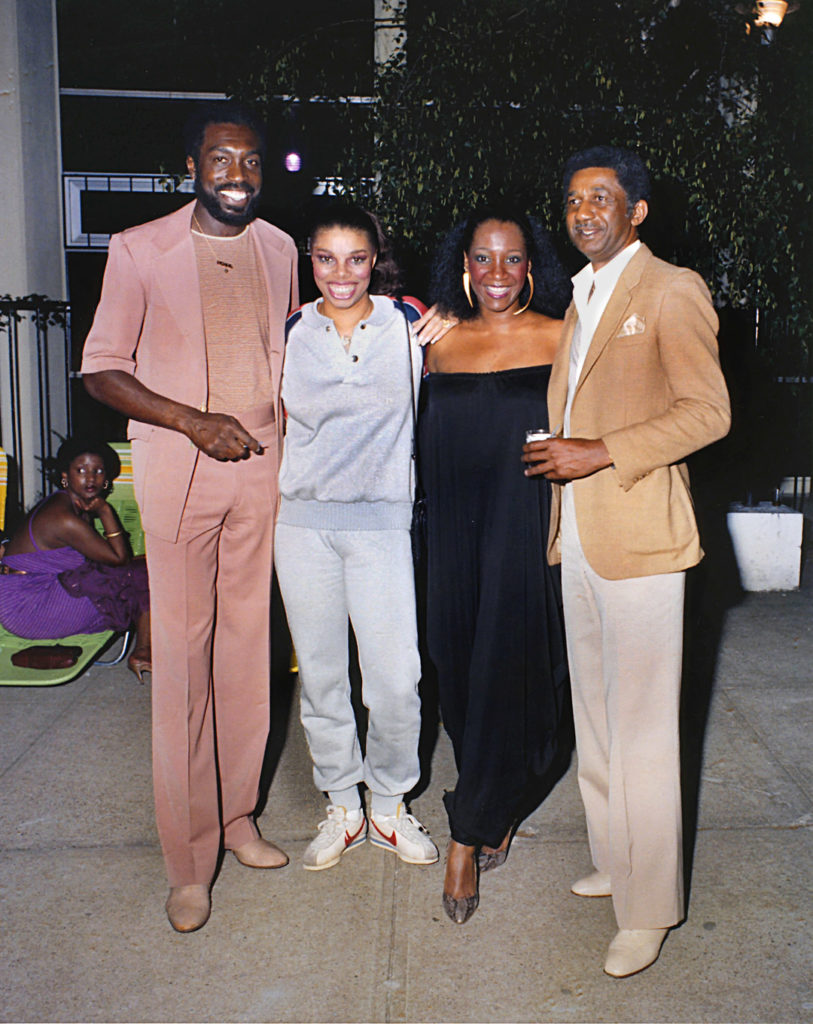

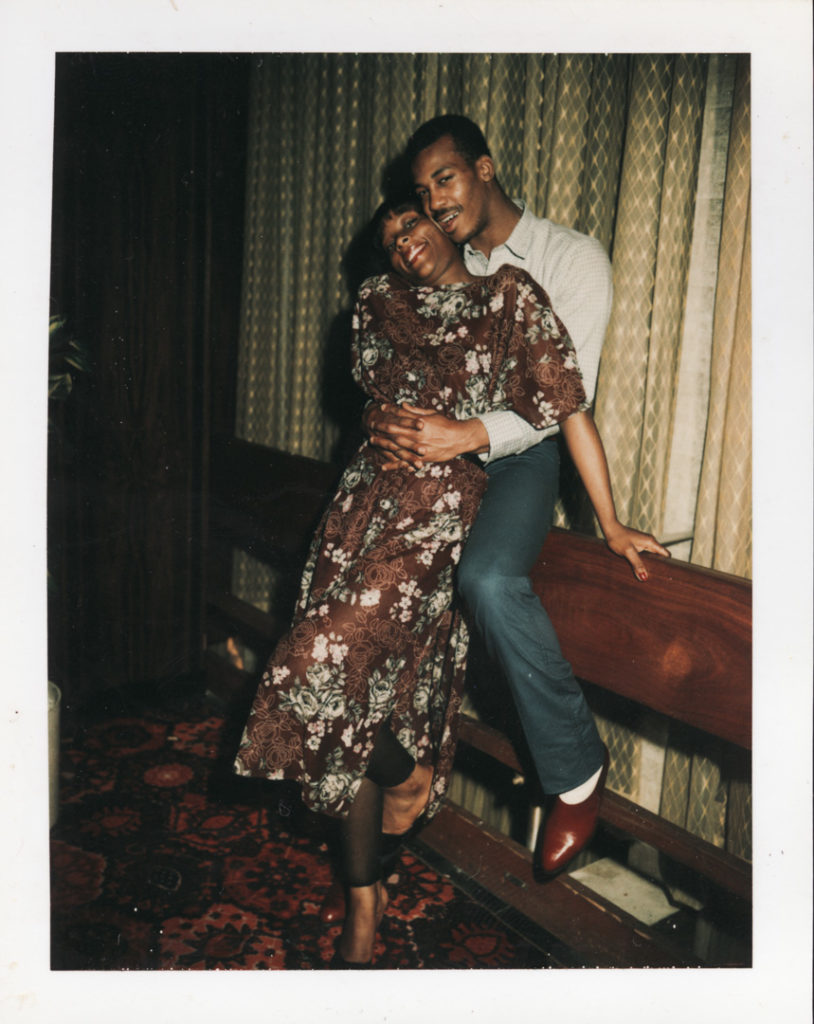

From left, Earl “The Pearl” Monroe, Millie Jackson, Patti LaBelle and unidentified companion at Zanzibar.

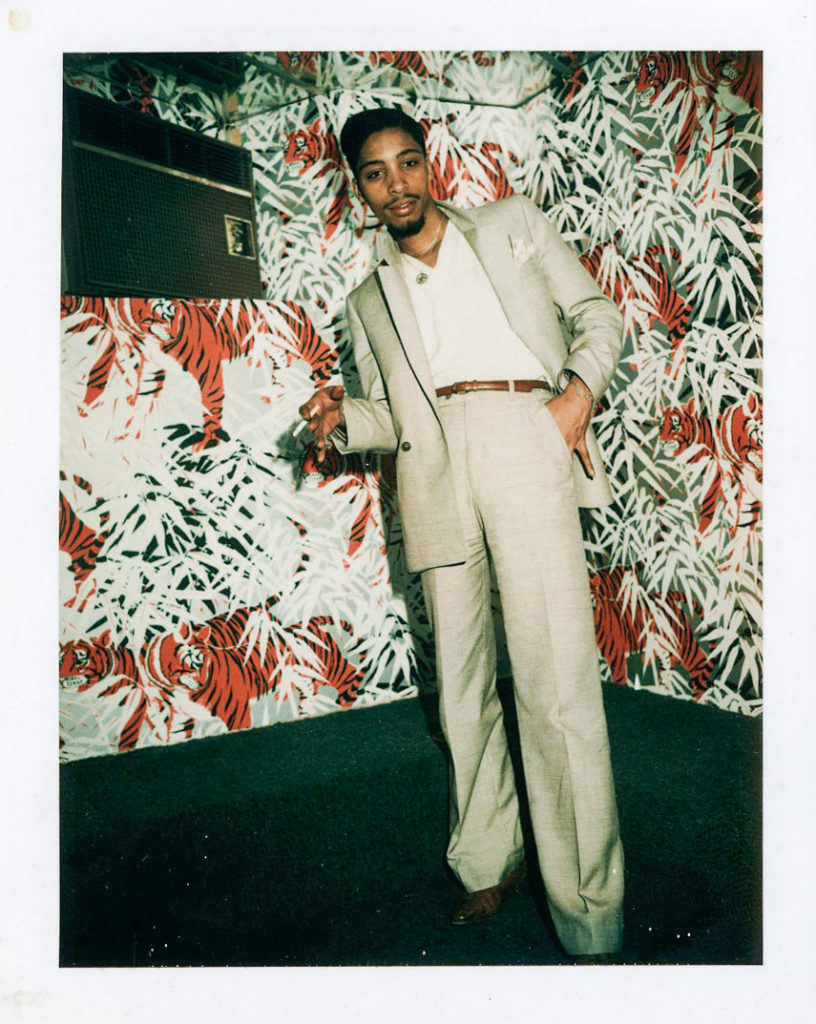

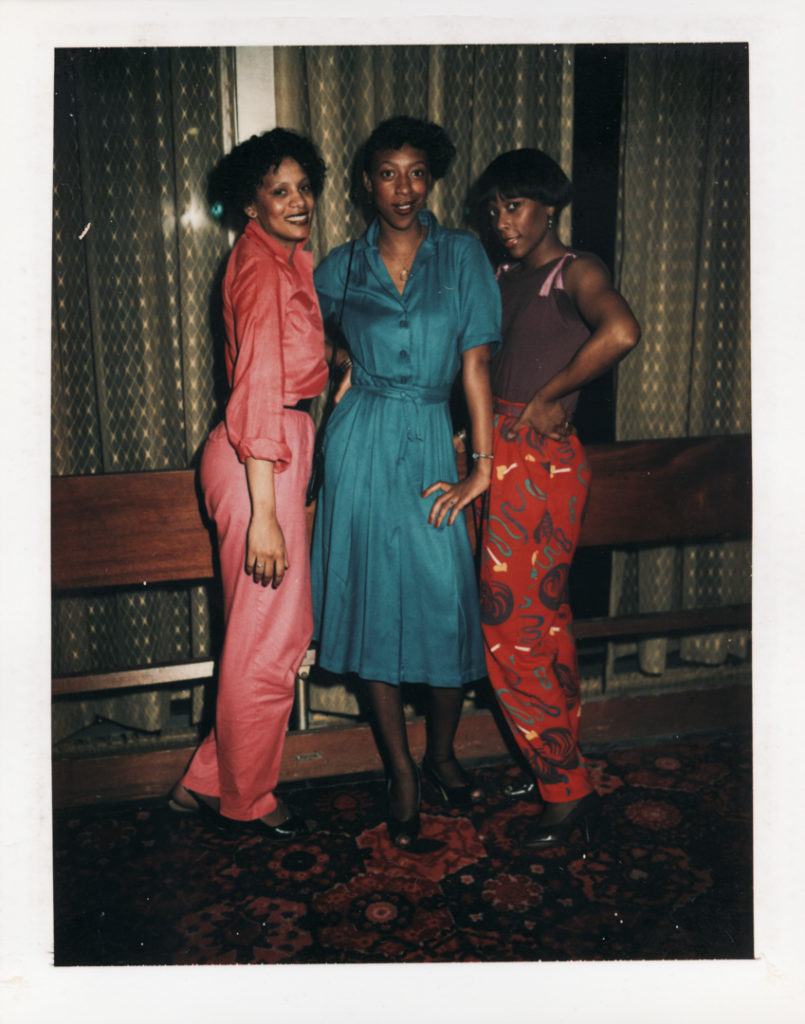

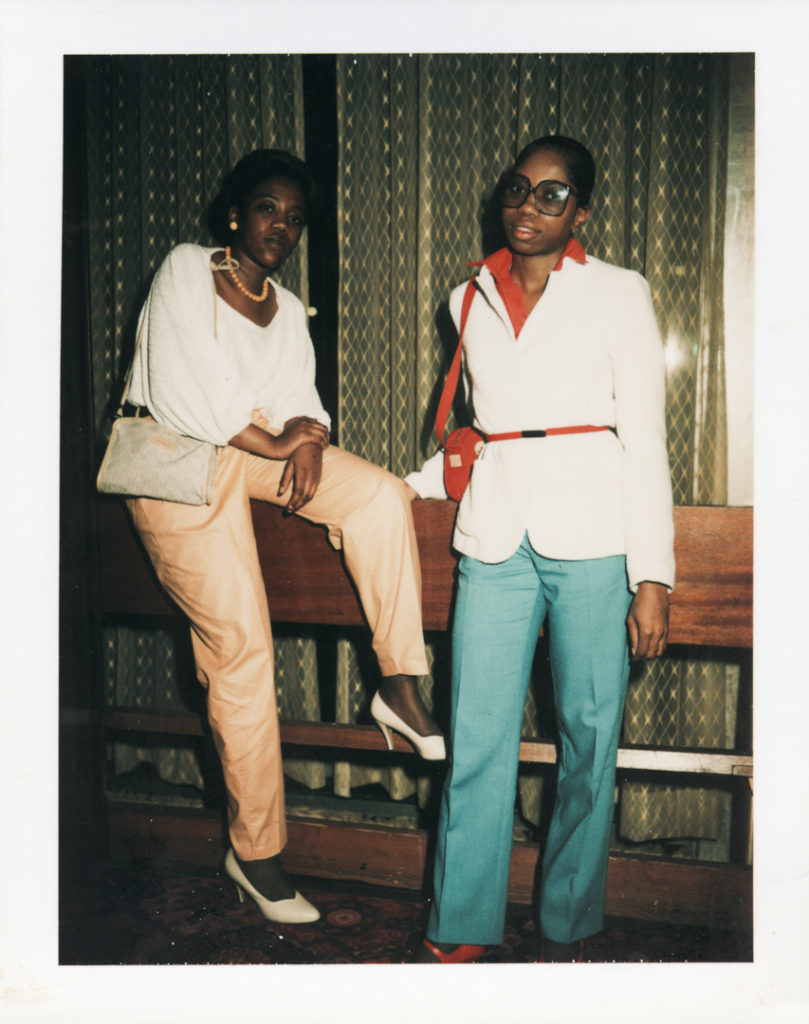

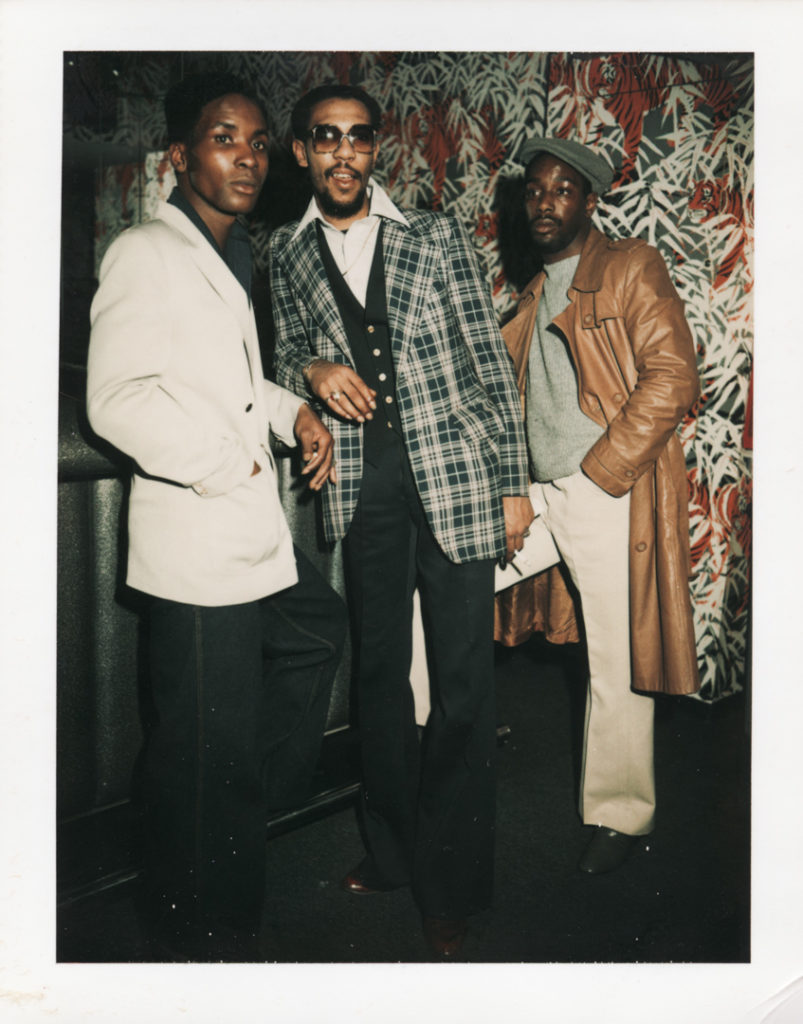

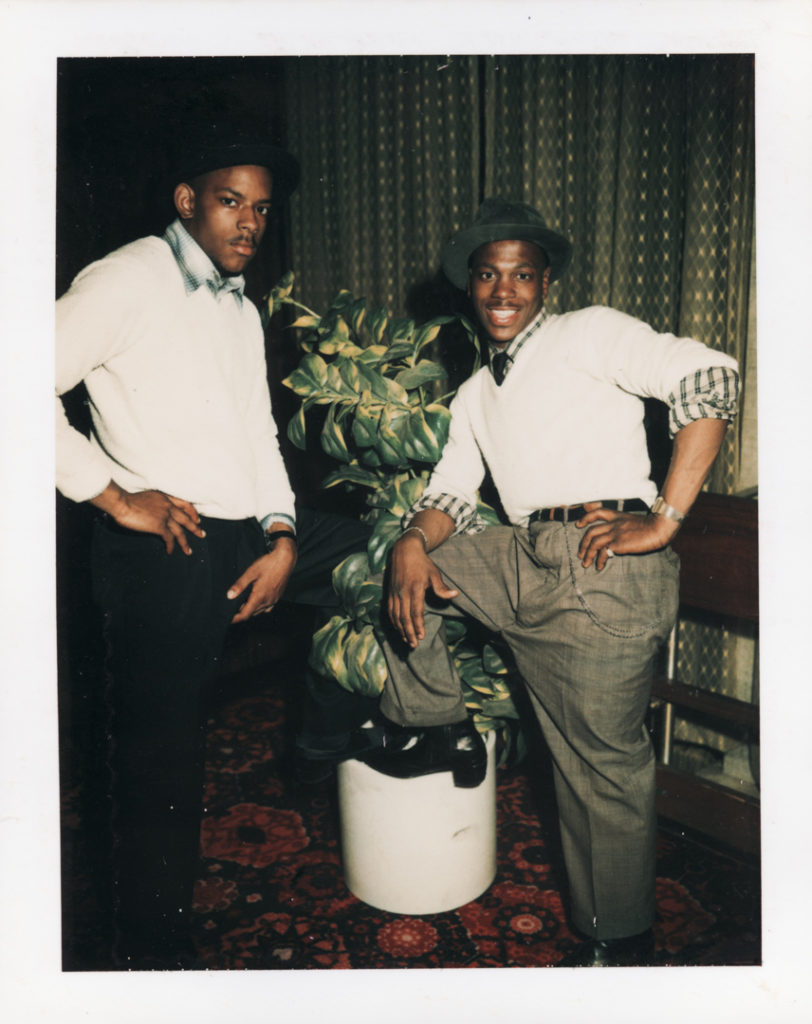

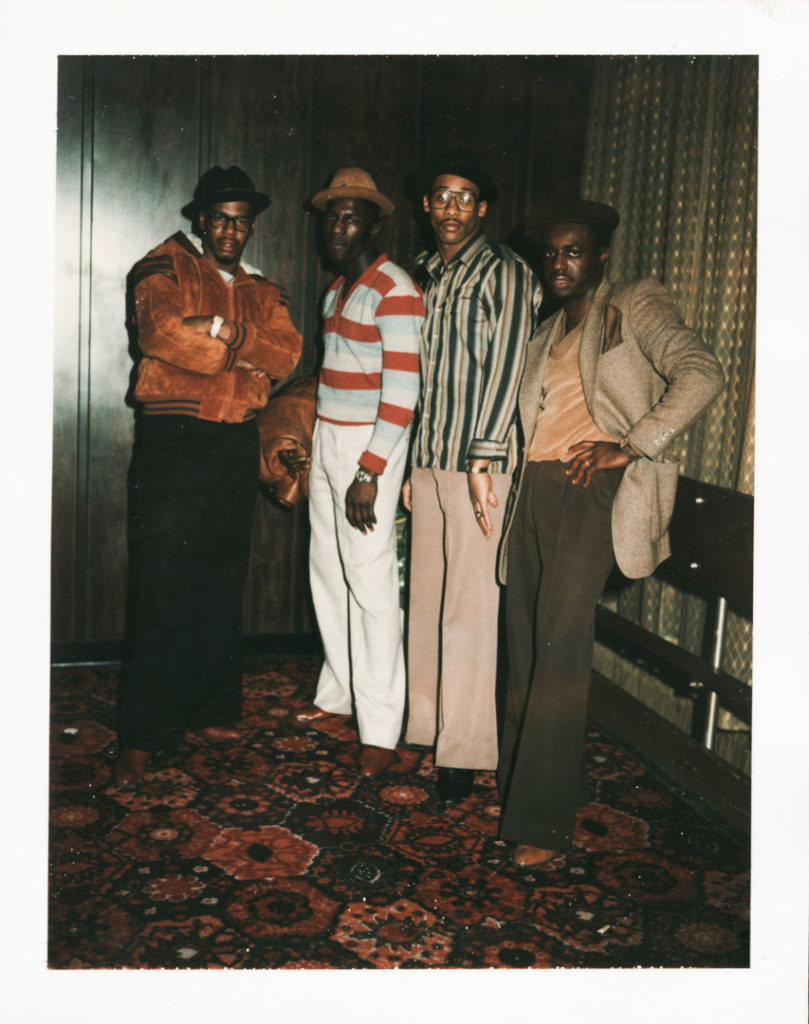

Vincent Bryant was Zanzibar’s house photographer and the only person allowed to take photographs inside the club. He also took Polaroids of the patrons, who bought them for $5 apiece. Bryant kept some of the outtakes, but the majority went home with people as souvenirs of their wild nights at The Zanz. Below are several of the images Bryant held onto.

Were you at Zanzibar?

We need your help to resurrect the glory days of Newark’s greatest nightclub. If you’ve got any Polaroids Bryant took of you, send them to us at studio@talkingeyesmedia.org and we’ll add them to the gallery.

Clubbing at Zanzibar

by Bruce Tantum

Located in a broken-down stretch of Newark, Zanzibar was the spot where famed spinner Tony Humphries rose to fame. The club – along with the Movin’ Records shop and label – helped spawn the sometimes raw but always soulful, gospel-infused subgenre of house known as the Jersey Sound. Zanzibar may have imported its sound designer from Manhattan’s Paradise Garage, but the distinctive sound created by the club’s DJs was Jersey fresh. But only its devoted patrons and nightlife historians know the rich history of the influential—and, to those who were there, beloved—club, which ran from 1979 until the early ’90s.

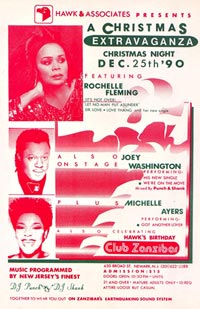

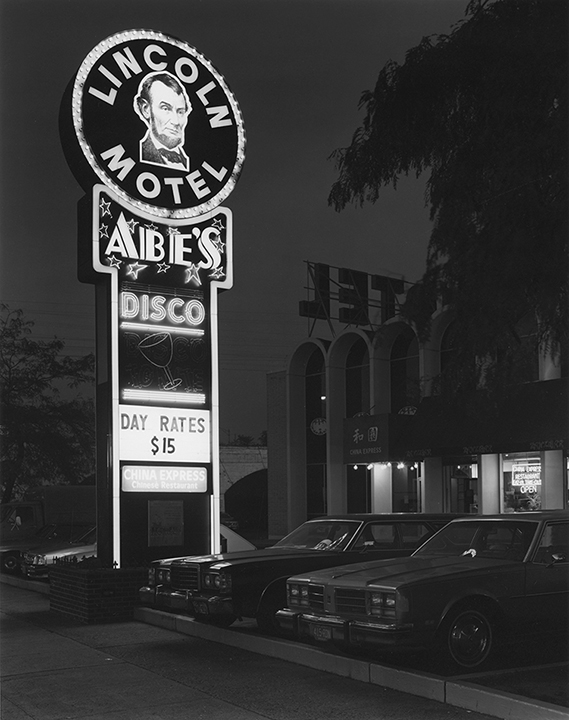

Zanzibar’s story begins in the mid-’70s, when Miles Berger bought a seedy Holiday Inn at 430 Broad Street, transforming it into the ever-so-slightly less sketchy Lincoln Motel. Within that building was a small dance club called Abe’s, which counted Gerald T and Hippie Torrales (the man who would later produce the 1988 house classic “You’re Gonna Miss Me”) among its DJs. When Abe’s outgrew its intimate room in ’79…well, that’s when things really started shaking. Sadly, quite a few of Zanzibar’s principal players—soundsystem man Richard Long; managers Albert Murphy and Shelton Hayes; and DJs like Larry Patterson, Tee Scott, and Larry Levan—are no longer with us. But plenty of the others are. Here is the story of Zanzibar in their words.

I was a day porter at the Lincoln Motel; I was about 17 at the time. The place was this gaudy, ’70s-looking kind of thing with burgundy carpets, red velvet all over, glass cut with little designs and a fountain – tacky, but not as bad as it could have been, like what “classy” would have looked like in a really bad Blaxploitation movie.

– Stewart Upchurch

I was actually playing at Abe’s before it was Abe’s, when the Lincoln Motel was still a Holiday Inn, back in ’75. I knew how to make Abe’s into a real club, but I didn’t have the money; Miles didn’t know anything about clubs, but he had the money.

When Abe’s opened, we were only getting like 25 people a night in there. You’ve got to remember, there were clubs all over back then; anyone who had a bar would get a DJ and call it a club, so there were lots of places to go. But my name was a little known – not a lot, but a little.

After a few months, I go to Miles, and I say, “You’ve got a ballroom upstairs. What are you doing with it?” He said, “I rent it out for $700 a night!” I said, “Why don’t we take this ballroom and convert it into a huge club, a club that will be immaculate? You could make that $700 back in five minutes every night!”

– Gerald T

Opening night, which was the Friday of Labor Day weekend in 1979, was huge. They did it right; they invited celebs and everything. WNJR Radio did a live remote, and Channel 4 was filming. People like Kool & the Gang were hanging out. Tasha Thomas was there. My main competition for attention was this monkey named Zippy. This monkey could roller skate to disco music! And Joe Robinson from Sugar Hill Records was there. A week before, he had brought the test pressing of this record to a radio station in Texas and they had played it, but nobody in the New York area had it yet. He was like, “I have this new record, and it’s a new style. It’s only been played by one radio station in Texas so far.” So that’s how we ended up breaking “Rapper’s Delight.”

– Hippie Torrales

That night was so incredible. The club was draped in vines – real vines – with live orchids placed within them. There were flowers all around. It was a real tropical kind of decor. And we had these animals, tigers and all of those, which were rented from Great Adventure. They were out back by the poolside. Newark had never seen anything like that. All of New Jersey had ever seen anything like that!

– Larkie Rucker (assistant manager and host)

Miles knew he had a success right away. He had invested hundreds of thousands of dollars, and one day I asked him how the club was doing as far as money goes. He said, “I made my investments back in the first six months!” Let’s just put it this way: He was a happy man. The guy was making money out the wazoo! But when Gerald and I were the residents, Miles used to pay me $40 per night as a DJ. And I only deejayed at Zanzibar one night a week. But I used to live in the hotel for free, so I guess Miles felt that it was a fair deal.

– Hippie Torrales

DJ Hippie Torrales

DJ Gerald T. Roney

After Al Murphy became manager, that’s when my woes began; he wanted to remove me and put in the kind of DJ that he wanted. I’m not saying because I wasn’t gay, but he wanted something else. The club was changing. We went from being a classy club where everybody had to get dressed up, to a place where people could come in dressed casual, so they could dance.

– Gerald T

Albert brought in Larry Patterson, who had been a DJ at Albert’s own little gay club, Le Jock, which used to be on Halsey Street back in the day. We used to partner up with Paradise Garage and brought in some really good acts. We brought in Five Star from London; we brought in Modern Romance and Central Line in from London, too. A lot of these people were coming over for their first time in the United States. Chaka Khan came through there a couple of times; Sylvester came through.

– Larkie Rucker

Al finally brought Grace Jones in, and that took everything to a whole other level.

– Billie Prest (manager)

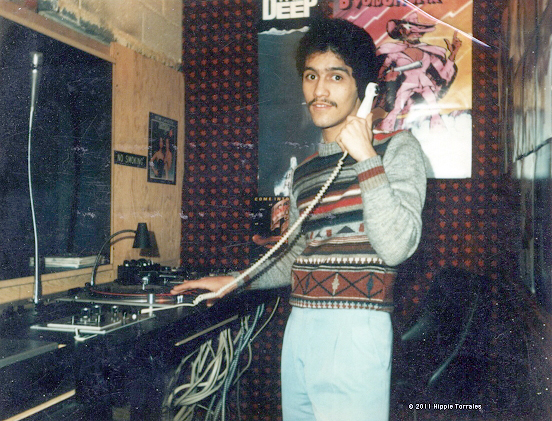

DJ Larry Patterson and assistant manager Larkie Rucker in full regalia.

Fonda Ray performs at Zanzibar.

I knew Larry Patterson, and one day he said, “You gotta check out this club in Jersey!” I was like, “Jersey! You gotta be kidding.” But Shep Pettibone, Jose Guzman – who was one of the on-air personalities at Kiss FM – and myself decided to take a ride out to Newark and check it out. I walked in and said, “Holy shit – this feels exactly like the Garage! I started hanging out there, listening to Larry Patterson on Wednesdays and Fridays, and Tee Scott on Saturdays. Finally I said, “Look, guys – if you don’t give me Wednesdays, I’m not coming back any more.” And that’s how I got into Zanzibar.

– Tony Humphries

Tony had a sound that was centered around underground Jersey house, and – before that – it was stuff that wasn’t quite house yet, like “The Music Got Me” by Visual. It was when all the Jersey producers were starting to come up. I would hear him play classics sometimes, but they were the kind of classics that would fit into the house groove that he liked.

– Danny Krivit

I think everything that went on at Movin’ Records transpired because of shit that happened at Zanzibar.

– Jon Martin

I’d know what Tony was playing, we’d know when it was coming, then we would have it in the store, and people would come in to buy it after hearing it at Zanzibar. Finally, Tony, Shelton Hayes and I decided bring some more focus to this great music that was coming out, this music that we had been starting to call the Jersey Sound. We did these parties at the New Music Seminar in 1989 and we were flabbergasted by the amount of people who came out – people from all over the world! They really liked the soulful, lyrical, spiritual-based sound – something that was different than what Chicago or Detroit that were doing.

– Abigail Adams (Movin’ Records owner)

Don’t forget, Zanzibar was in, like a crack hotel, and if you went there at 11 PM, it was thugged out. If I got there early, I would feel uncomfortable. If it wasn’t for the fact that Shelton was on top of things, it might have been rough. But the room would get gayer and gayer as the night went on, and there would be no judgments.

– Jon Martin

None of my New York friends wanted to make the trip, so I would just take the train, my Jersey friends would pick me up, we’d go to the club to party – I don’t drink or do drugs, but I do dance! – and I’d spend the night, and go home the next morning. I don’t remember seeing a fight there, ever. It was the kind of place where the music, house music, could generate a kind of love energy, so it was a wonderful place to be.

– Barbara Tucker

After I finally got back from that time in London, the club had changed a lot. It just wasn’t the same. They had finally decided to make it a very hip hop-friendly place, and changed the name to Brick City.

– Tony Humphries

Once Zanzibar went hip hop, that was it. There was fighting, stabbings, all kinds of stuff. I was happy that I was out of there by then.

– Gerald T

Not long after that, the club closed down; finally, in 2007, they demolished the whole place. When I look at the pictures of the building being torn down, I just remember all the good times I had there; we were like family.

– Larkie Rucker

I get really emotional when I talk about it, but that club means everything to me. It was such a big part of my life, and it’s the kind of place that we’re missing today. We’re missing that kind of vibe where everybody would just get together and have a great time. And to me, that’s really what house music is all about.

– Gladys Pizarro