I. The story

That October morning, a group of 58 people, mostly older women, gathered at the gates of the U.S. Embassy in Mexico City. All had their bags packed, many with stiff newness that crackled in the morning chill. Some of the people lined up had left their small towns, their farms, animals and families, a full 24 hours before, in order to arrive at these gates.

They were all notably nervous, speaking in Nahuatl, Mixteco and Spanish, sometimes laughing, sometimes crying. Most of the women had been attending weekly committee meetings for at least a year, and some for as many as five years, in anticipation of this day. At these meetings, they learned about human rights and the root causes of migration, practiced the indigenous dances of their villages; tasted each other’s recipes of rich local foods like mole and pipian, and wove baskets in the style of their great grandmothers.

They hoped that today they would get the long-awaited news that they would be able to travel to the United States.

All the women had relatives in the United States, many of whom they hadn’t seen for more than 15 years. The women had missed marriage celebrations, the ability to mourn and comfort the sick and dead with their children, and the birth of grandchildren. They came from communities that had been emptied of many of their young men. Without work to support their families, the men had been forced to the north.

This morning the U.S. embassy would decide if they would be granted visas to attend a cultural festival in New York, called NYTlan, where they would share the work they had been doing in Mexico. And where they would be reunited with their family members.

Justina had been granted a visa for the previous two years to attend NYTlan, and she hoped that this year would be no different. But she sensed that the interview was going badly. The embassy agent she met with had seemed uninterested in the festival. And she was right. The official told her she was denied.

Mariana, on the other hand, saw the same official right after Justina. They had seemed relatively friendly, and even though she had been previously deported, she was granted a visa.

The Popular Association of Migrant Families (APOFAM) has been organizing similar events for the past four years, and nearly 80 percent of requested visas have been granted.

This year APOFAM organizers, together with their partner at Rutgers-Newark, had planned to hold an event reuniting the 58 women with their family members on Friday, October 13th.

There were early signs this year would be different: the request for a visa interview with the U.S. Embassy, usually granted quickly and without hassle, was initially denied and had to be appealed – delaying the visa interviews to just two days before the event.

As the women wept, 31 with relief and 27 with grief, the seeming randomness of the visa denials struck the organizers as particularly cruel. Not only had the number of visas granted been lower than ever before, they seemingly were granted on a whim.

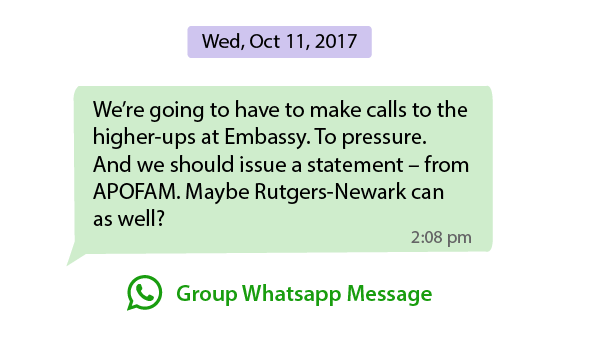

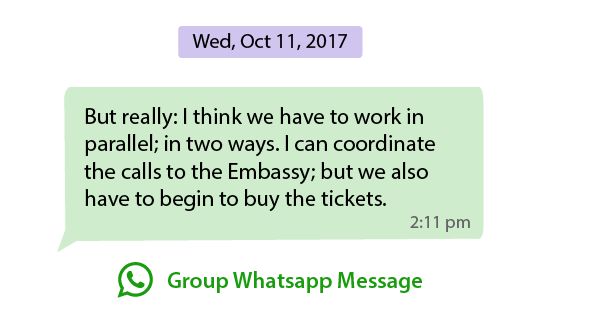

While some APOFAM and Rutgers organizers strategized appealing the decisions, others began the urgent task of purchasing tickets for the women who would travel to the United States the next night. Before their plane left they needed to purchase plane tickets for those granted visas, pressure the Embassy to return their stamped passports by 5pm the following day, and notify their families that they had been approved in time to catch a 7pm flight. Complicating matters further, their visa interviewer didn’t tell them how long their visas would be valid: they would learn this crucial detail less than two hours before they boarded the plane.

The women denied visas would take their packed, still-new suitcases and return home.

II. Three years to get to the line

Cecilia lives in San Jerónimo Xayacatlán, Puebla, an indigenous community about five hours by bus from Mexico City. She normally wakes up at 5am to feed and clean her chicken and pigs, and dedicates the rest of the morning to cleaning the house.

This takes longer than it used to: her house has grown from a small shack made of corn stalks and earth to a spacious two-story cement and brick house thanks to the money her four sons who are in the U.S. have sent her.

Cecilia first heard of APOFAM from her sister-in-law. After learning there was an organization that might help her see her children in the U.S., she was both excited and hesitant: while she wanted nothing more than to see her family, she worried that this group, like many others, would turn out to be less than it promised.

When she first started attending meetings in 2012, the group of about 15 women reflected on what their strengths were: what did they have of value to share with the world? They decided to learn a traditional dance performed during Carnival with the hopes that they would be able to perform it at NYTlan. While she had seen the dance since she was a young child, it had primarily been performed by men – and she was excited to show that women could do it too.

The group also opened a Mixteco language after-school program for the children. While Cecilia had grown up speaking the indigenous language of her parents, her children had not. At this school, they promoted respect and knowledge of Mixteco culture. Their strategy: get students in the door by cooking delicious traditional food, and then teach children the almost-lost Mixteco language.

Apart from these community activities, the group also studies how to navigate the complex and daunting paperwork necessary to apply for U.S. visas.

Cecilia left school at ten years old, and the idea of obtaining a birth certificate, oftentimes a complex process because of missing or incorrect birth dates and misspelled indigenous names, much less getting a passport, previously seemed impossible. The APOFAM organizers, mainly young and college-educated, teach them how it can be done.

APOFAM was born out of a project called IIPSOCULTA: The Institute for Social and Cultural Practice and Research.

Marco Castillo, a Mexican anthropologist from the state of Puebla, founded the organization in 2001 after being inspired by the ideas of human rights and self-determination of the Zapatistas. He began to work in some of the poorest, most isolated communities in central Mexico, all of which had large portions of their young people working in the U.S.

After living and working in these communities for several years, it became clear to Marco that family separation due to migration was a daily, gnawing stress. People were suffering from anxiety, depression, alcohol, drug addiction and other mental illnesses due largely to the absence of their family members.

This stress meant that people were willing to sacrifice whatever they needed to in order get the resources together to bring their families together, including saving all their money sent from the U.S., working extensive hours for very low wages, and postponing medical attention.

IIPSOCULTA set out to address the devastating impacts of separated families with a two-part strategy. First, it would work to empower the mostly indigenous women in underserved communities to improve their lives. Second, they worked to reunite families after decades of separation. Today, almost 200 families are part of APOFAM local committees in four states in Mexico, and nearly 100 have been reunited with their family members in the United States.

Each local committee elects leaders to attend community organizing workshops, and selects members of their group to represent them at NYTlan and make the trip to the U.S.

A month ago, Cecilia was elected by her group to make the trip to the U.S. for the first time. Her group commended her for her high attendance at their events, and her leadership in running the Mixteco school. She is excited to perform the Carnival dance, sell the baskets she made together with two other women in the group, and to cook her signature dish and sell it at NYTlan. She is also very, very excited to see her sons, three of whom have had children she has yet to meet.

Cecilia was fourth from the back of the line outside the U.S. Embassy – and despite the many denials issued that day, she is one of the lucky ones: her visa is approved.

She will travel to New York tomorrow to see her family.

III. The Reunification & The Vision

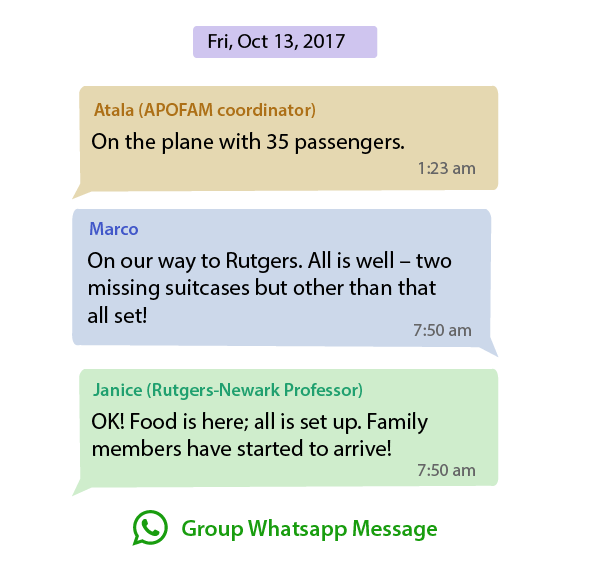

A little after 9am on October 13th, 31 APOFAM members get off their bus and enter the Rutgers University-Newark Law School building. Inside, a perhaps unlikely welcoming committee is gathering: family members of the Mexican women; Rutgers students and administration representatives; and other community supporters like La Colmena, a NYC worker’s center who has supported APOFAM for years.

This gathering of just more than 100 people soon lines the rows of the Law School classroom, clapping and crying as each traveler makes her way, often haltingly and with a gait that betrays her years, towards the center of the room where her family member awaits.

Marco Castillo, IIPSOCULTA’s founder, and Atala Chavez, APOFAM’s Mexico-based coordinator, work together to introduce each family member. Janice Gallagher, Assistant Professor of Political Science at RU-N, translates some of their remarks into English for the assembled students and administrators.

Marco, Atala and Janice – the senders of the Whatsapp messages – met five years previously in Mexico. They all participated in a social movement led by family members who had been victims of violence during Mexico’s escalating drug war.

This APOFAM-organized event is responding to a different type of violence – but one which all three see as devastating to communities on both sides of the border.

The debate over Mexican migration in the U.S. has been dominated by divisive and hateful talk of the security threats of Mexican migrants and the danger they pose to American workers.

“We want to see a U.S. immigration system that is based in the American tradition of family unity and human safety.”

APOFAM is part of a larger movement focused on putting American and Mexican families at the center of relations between these two countries.

Like the Sanctuary movement of the 1980s, family reunification goes beyond simply mitigating the harsh conditions experienced by immigrants or seeking to change policy.

Family reunification shifts attention to the humanness behind the demand of rights for all migrants in the U.S., moving the debate away from national security to the heart of the migration issue: family love.

For the organizers, this vision has direct implications for immigration policy. In APOFAM’s words:

“We want to see a U.S. immigration system that is based in the American tradition of family unity and human safety. That system should be expressed in the criteria that consular officers use to decide whether or not to give travel documents to an individual with no criminal record, proven community leadership, and interests and relations in both countries, regardless of income, ethnicity, gender or age. This should be established in the ruling documents of the Department of State, based on the constitutional grounds of justice and democracy.”

As part of this organizing model, APOFAM founded the Transnational Villages Network as its mirror in the U.S. In these groups, the family members of people like Justina, Mariana and Cecilia, who live in the United States, have begun to meet to address the challenges they face as migrants.

As these groups become stronger, they have begun to think about how to organize in both countries for things like better wages and justice – which they understand as the right to be close to their loved ones; the right to have their families together.

They have also begun to recognize their own economic, cultural and political strengths and contributions. Ultimately, APOFAM believes that it is possible to organize trans-locally, among towns and cities of origin and destination, in a way that can accelerate access to justice, economic opportunities and rights through common agreements and shared commitments.

Days after the event, one of the RU-N students who attended the event reflected that seeing families reunified made her question “who separates a mother and a father from a young daughter?…While I know this immigration system in our country is absolutely screwed up, this really gave me a better idea of what that really means, and affirmed the idea that we have work to do together to change things.”

A tenacious problem in the immigration debate has been how to change people’s minds. As organizers, as teachers, and as citizens this event touched our hearts. We see potential transformation in both.