When Mohamed Hassan arrived in Malta with his family nine years ago, he was shocked by what he experienced. He, his mother, father and four siblings arrived by plane from Saudi Arabia and were sent to Hal Far refugee camp, where they lived in a shipping container for seven months. Hassan, who is Eritrean, assumed that a country in the European Union would receive asylum seekers with dignity and modern accommodations. Instead he saw sub-human conditions and watched another family’s belongings thrown outside the container to make space for his family.

For a small island, Malta is expected to pull well beyond its weight in receiving refugees. Historically, it has played a major role in the story of human migration, but the influx of people over the past three decades has challenged its institutions, often with grave results.

Located in the Mediterranean Sea just south of Sicily and only 680 miles from the coast of Libya, it has been a strategic spit of land for millennia. Its coordinates place Malta at the crossroads of power dynamics between Europe, Africa and the Middle East. It has been controlled by the Phoenicians, Carthaginians, Romans, Greeks, Arabs, Normans, Spanish, French and British. This tiny parcel of rugged rocks is perhaps best known as the dominion of the Knights of Malta, who were given the island by King Charles V in 1530 to help fend off the Ottoman Empire. While its language and heritage share deep connections with the Arab world, centuries of Christian rule have all but eradicated any traces of Islam — until recently.

Over the past three decades an influx of refugees has altered the face of this island. They started arriving in the 1990s in boats and dinghies, predominantly young men fleeing war and poverty. They came from global hotspots like Somalia, Iraq, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Libya and Syria, and they were desperate to reach Europe to start new lives. For them, Malta was nothing more than a transit point, a stopover on their way to mainland Europe, a place they barely knew existed. But for many, that journey stopped in Malta, where they now live in a state of limbo.

“I would say in the very early days there was a sense of compassion: What is going on? Why are these people coming here? But it shifted very, very quickly,” says Maria Pisani, Director of Integra Foundation, a refugee relief organization based in Malta. “Since 2002, what we’ve seen throughout Europe is a race to the bottom with these borders and fortresses—physical and metaphorical – being built up every single day.”

In 2002, Malta joined other countries in the European Union in signing the Dublin Regulation, which mandates that people who arrive in the EU and apply for asylum must remain in the country where they applied. This put a tremendous burden on Malta, which has received a disproportionate number of asylum seekers compared to its population. Malta has had a refugee policy in place since 2001 and as a member of the EU must follow EU guidelines. The problem is that like many other EU countries, they don’t always follow the policy. Malta has periodically refused asylum seekers from docking, stranding them at sea for weeks at a time. The country also has forced boats to return to Libya, where refugees will face dire circumstances if not certain death.

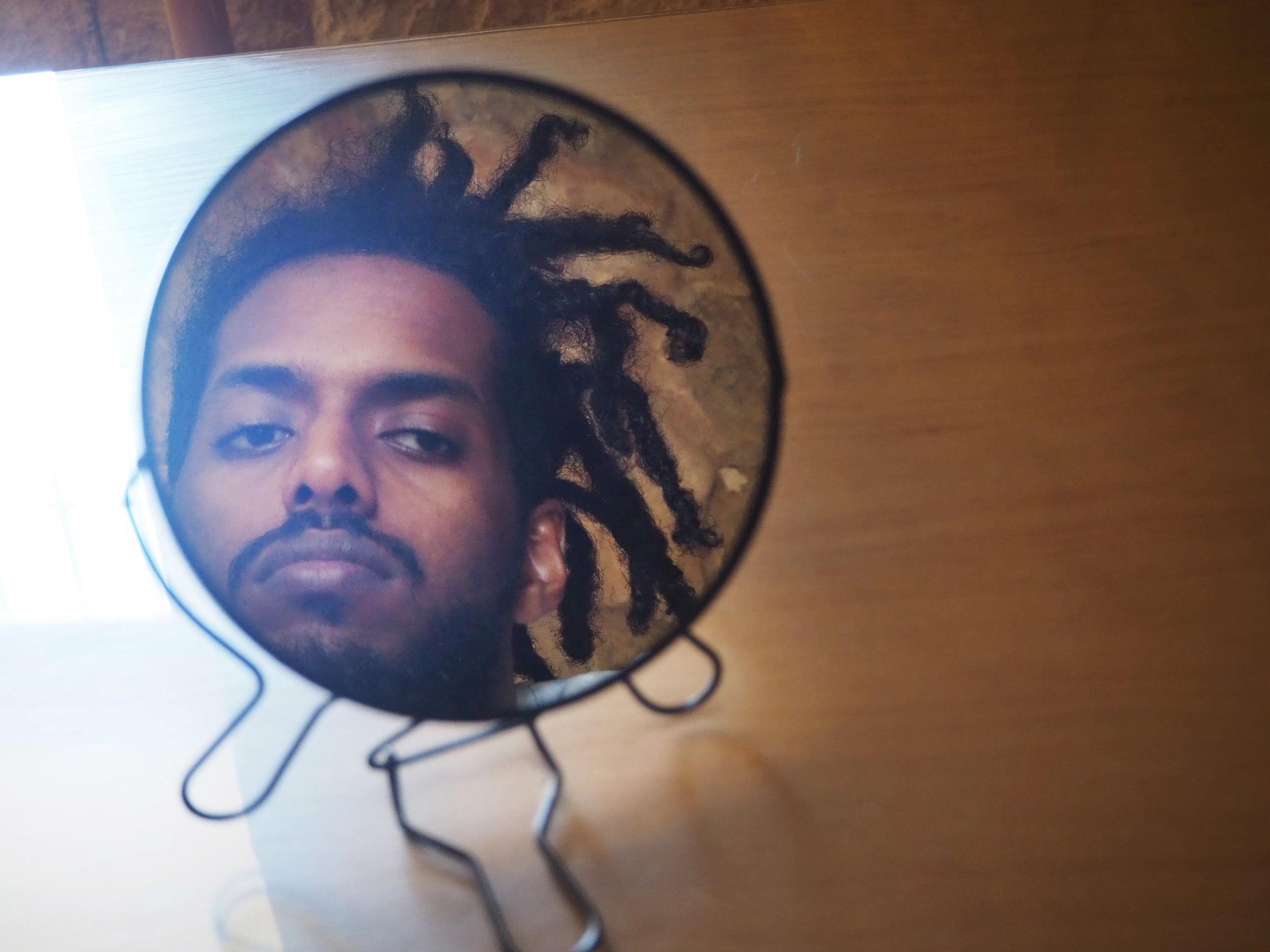

In the summer of 2019, Newest Americans partnered with National Geographic Photo Camp and Integra Foundation to conduct a photography workshop with young refugees in Malta. The five-day intensive program led by Newest Americans co-founders Julie Winokur and Ed Kashi, in collaboration with National Geographic staff had participants fan out across the island to document Malta through their eyes. The result is quite different from the picture postcards usually seen of this vacationers’ paradise.