A conversation at the restaurant 27 Mix inspires a look at Newark’s history through the racial hieroglyphics etched on hand-me down shirts.

One of my favorite haunts in University Heights is 27 Mix on Halsey Street. I wrote and edited much of my dissertation there while drinking Hennessy and Coke. It is also the place where I’ve heard some of the best stories about Newark’s history. Many of the regulars are long-time Newark residents. The kind of folks who can tell you what the very building you are standing in used to be before it became a classy bar and restaurant. What it was like to live in Newark when it was a city of black people under siege by the police.

I’ve heard some of the best stories from my good friend Greg. Greg grew up near South Orange Avenue and Springfield, on 7th street, where he lives now. He has lived an exciting life and traveled all over the world. But somehow he ends up back here, in Newark, at 27 Mix telling me stories of the way things used to be.

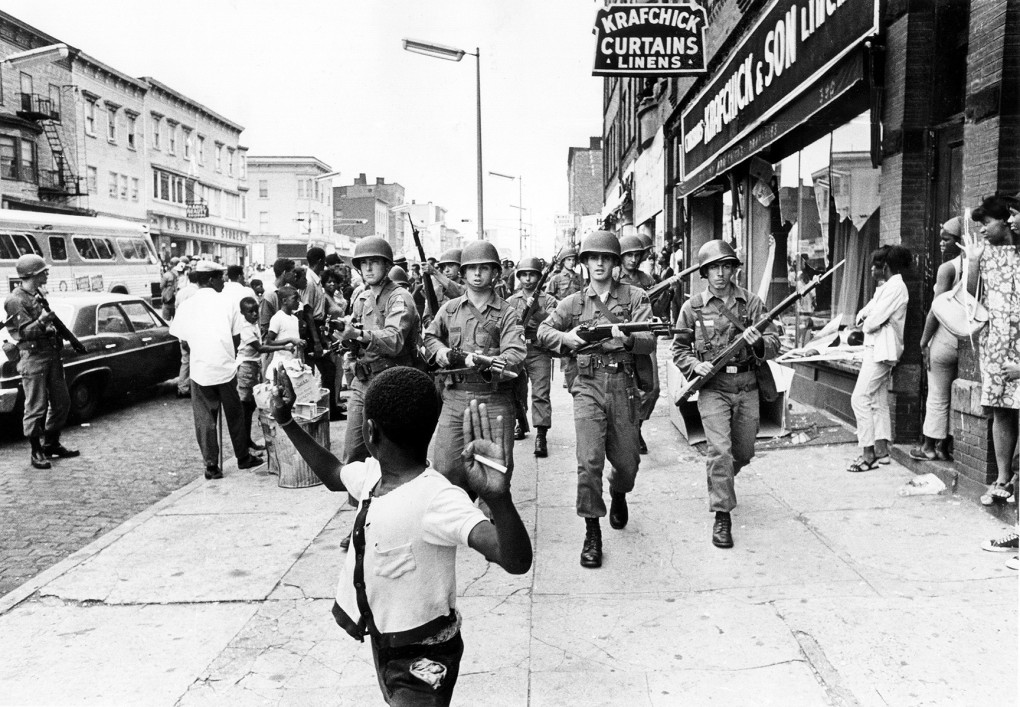

Greg was eleven when the Newark uprisings happened. He remembered seeing white police officers with guns on rooftops. Being told by his mother not to stand in front of windows. When I asked (like some kind of neoliberal journalist) what race relations were like in Newark at the time, he said there was no such thing as race relations. Everyone was black. Well not quite everyone. Teachers were white. Cops were white. And many black women in Newark, like Greg’s Aunt Theo, worked for white families as domestics.

A domestic worker in Newark could very well have prepared meals and cleaned the homes of the same people who pointed sniper rifles at their sons and brothers.

And then there was Dennis Okin. At first, to Greg anyway, Dennis Okin was just a name. It was etched into many of his t-shirts and collared shirts. Greg thought Dennis Okin was some sort of exclusive designer that no one in Newark had discovered yet. In reality, Dennis Okin was the son of Aunt Theo’s employers. He happened to be the same age and size as Greg. It was (and still is) very common for white families to give things they no longer needed to domestic workers. Called cast-offs, these “gifts” were often given in place of wages. The reality, however, is that boys grow fast. Greg probably grew out of those shirts as fast as Aunt Theo could deliver them. It was just a part of life, he told me.

But his nonchalance about these hand-me-down clothes didn’t stop Greg from at least being curious. He didn’t know who the Okins were or where they lived. But he always wanted to meet the boy whose name was etched in all of his shirts.

My curiosity, however, is really focused on Aunt Theo. While white people remained a mystery to Greg, the intimacy between domestic workers and the families they work for has always fascinated me. A domestic worker in Newark could very well have prepared meals and cleaned the homes of the same people who pointed sniper rifles at their sons and brothers.

I can tell you from experience that history looks awfully different through the eyes of domestic workers. They know what the lives of people who spat on and threw rocks at civil rights organizers looked like when they put down their bats, sticks, rocks, and rifles and returned home to their families. They heard private conversations that were only whispered about in public.

I have had many conversations about Newark’s history with people at 27 Mix over cocktails. Many of these stories begin with an aunt or grandmother who worked as a domestic. But none of them intrigued me more than Greg’s. The idea that “race relations” in Newark through the eyes of a young black boy living in University Heights amounted to nothing more than a name sewn into his hand-me-downs. I wonder how many other Aunt Theos there are with stories to tell. But for now my thoughts have at least been rescued from the cutting room floor and found a place here amidst Newest Americans’ meditation on the history of University Heights.