A Photograph

1998. In my third year of college at the University of Chicago, my Urdu professor, C.M. Naim, asks me one day during a class break, “Where are you from?”

Our class is held in his small corner office with a wooden table surrounded on all sides by filled bookshelves. Urdu is a dying language of North India, a blend of Sanskrit, Persian and Arabic. My classmates have scampered for bathroom, smoke and coffee excursions. For months, I struggle in his class, repeatedly and wrongly conjugating Urdu tenses. I invoke his wrath when I despoil the language. Most of us in the class with South Asian heritage, born in the U.S., do not know our mother tongue with fluency.

“My parents were born in Mewat.” I reply. “A cluster of villages outside of Delhi that even those in Delhi do not know about. They don’t speak ‘pure’ Urdu there but a local dialect.”

He raises his eyebrows. C.M. Naim is a leading Urdu scholar in the U.S., if not the world. We are studying Urdu from the textbook he has authored.

“Yes, I know of Mewat. Even I would have trouble understanding that dialect.” He says gently. “Interesting. You have a very interesting history. You must read about it.”

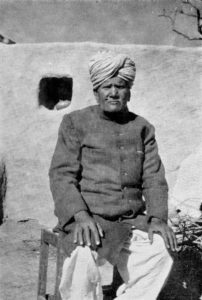

He compels me towards the Regenstein Library’s fifth floor stacks, one of the only collections in the world that brims with so many obscure books on South Asia. That afternoon I am the only person there, lost in rows of metal shelves under dim lights. As I fumble through cloth-bound, hardback texts, an overexposed black and white print photograph in Pratap Aggarwal’s Caste, Power and Religion, stares back at me. In the quiet light of this behemoth library’s book stacks, I find a familiar face.

I know this man.

The college librarian, eyes squinting above her reading glasses, interrupts me. She is standing at the far end of the shelves, bellowing, her warning resembling a reprimand: the lights have to be shut off. Now it is just the two of us in the fifth-floor book stacks.

A folded white paper with the book’s reference code floats like a feather to the ground.

I leave Caste, Religion, and Power, on the shelf, too much to hold for one day, and venture outside. Snowflakes dissolve into my black coat. Ice crunches beneath the soles of my black boots. How strange and eerie these Chicago winters seemed at first; I did not even own a winter coat before I moved to this city. The wind now howls and cuts past my cheeks. The night is starless, wondrous.

In Caste, Religion, and Power, I encounter my grandfather’s picture. My grandfather is Yasin Khan. He is born in November 1896, at the cusp of a new century in Mewat. Mewat is a geographical area in north India spanning the states of Haryana, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh. It is distinct because it is home to the Meos, a Muslim tribal group. The Mirasis, North Indian folk storytellers, say that the Goddess Bedmata inscribes unique lines of destiny on Yasin Khan. He dies long before I am born.

After college, in the years to come, I gather stories about him, but at the time I encounter his photograph in the Regenstein Library, I only vaguely know that he is my grandfather.

Over several years, I learn about his role in the 1930s peasant resistance against the hike in agricultural taxes. His fight with the Raja of Alwar. How he is crowned chieftain of the Meo community. His construction of the first high school in Mewat with a sympathetic Britisher. His struggles in the Indian Independence Movement and efforts to stop his people from leaving their land and migrating to Pakistan during Partition. How the Yasin Brayne Meo High School that he helps to construct becomes a home for Partition refugees. The terrible grief at his death that spreads through thousands of people in hundreds of villages, widowing all of Mewat. In the backdrop of current seismic social and economic shifts in Meo villages, I do not know how to make sense of it all, except to gather story after story.

After seeing the photograph, shame crawls over my body. Shame rises from the pores of my skin and remains on the tips of my arm hair. It is a shiver that is not part of winter. I am not sure where the shame stems from, only that my life is incongruous. The flitting around. The socializing, the banter constrained to one level of conversation. When I first move from my hometown in Florida I hate this cold city and college, wildly homesick, but now I am caught in the mirth of social gatherings. I was never all that indulgent, never that wild, but indulgent enough to feel a guilt that tugs. But guilt based on what, even I do not know.

The guilt of frivolity, I finally realize. I return to the book stacks. Again, a piece of paper floats to the ground.

The guilt of ignorance.

I tell my roommate about the photograph. Her parents, Chicago suburbanites, hail from a remote province in northwest Pakistan.

“He looks Pathan,” she says, referring to her own background. Together we stare at my grandfather’s picture. We do not say much more about the photograph or the text.

At the University of Chicago, the checkered black and white floors of the Music building connect the Philosophy and Humanities buildings. During my third year, as I rush from one class to another, I hear a piano playing Chopin. It is a sonata I had also learned to play, soulfully, body leaning into the piano, if never entirely well or completely. As I rush to class, my mind darts through readings in theory. Theories of syncretism, lost histories, postcoloniality, subject and text, observer and observed.

These theories coalesce when just a few weeks later in my South Asian Civilizations class, we watch a documentary about agricultural women laborers in northern India. The women could be from my parent’s village; one even resembles my aunt but with a chipped tooth. We visited these villages for harried two-week stays every few years and me, keen to photograph each piece of it even then. Dung-caked huts and women in purdah, their long dupattas, practically down to their waist, a long drape of billowing cloth. The men, in turbans, crouching, smoking bidis. At sixteen, I knew that these images all had to be captured, viewed again in the red light of a darkroom on a print that floated in a developing tray. Prints collected in shoeboxes, negatives with frayed edges accumulating.

Now as a college student, I do not know whom to tell about this confrontation with the past. If I can even admit my simultaneous elation and shame. Others I meet hardly have any relatives back in India or if they do, they live in posh residential urban areas, still partial mirrors for their diasporic counterparts. In contrast, many of my relatives reside in villages. Or should I proudly proclaim, I come from a lineage of the oppressed, the enslaved, the rebellious…what I really mean to say is the broken-hearted.

In the auditorium where my South Asian Civilizations class is held, the women on the screen are subjects wrapped in a cellophane of patriarchy, liberalization, and resistance. I do not know what all this means only that something thumps beneath my blue and white blouse. My father always wanted me to study at Oxford; for Indians, the sign of a true elite education. I had after all grown up playing Chopin, experiencing such intimacy as if the music had been crafted and recorded for me. Now, in class, the very nearest to me are being excavated, displayed, discussed so as not to be forgotten. Only were they ever known?

I can see the piano music: stray sheets of five-bar lines filled with dancing black circles coupled with stems, some of the stems possessing leaves, being wildly strewn across the checkered black and white floors of the Music building. A different music and language is leading me elsewhere. I feel myself leaving one world and set of concerns to enter deeply into another.

Soon after, I return to my parents’ home in Florida. I confront my mother in the kitchen. We are always in the kitchen. My mother is in a long, flowery nightgown holding a ladle in her hand. She stirs a pot as she gazes at the television screen, usually an Indian soap opera she watches with fixed intensity. Her mouth is slightly open in alarm at the events unfolding on the celluloid.

“I never knew him. You never told me who he was,” I insist. I pace between the dining room and the kitchen. I pick up a napkin which I dangle and pretend to clean surfaces.

“That is not true. How else would you recognize him?”

I want to say that I thought you were illiterate, unknowing. I even thought you were a fool. My brothers and I called her a simpleton with her stories about the village, as if the village could be anything more than a place without electricity and roads. I never believed her stories could rise from the page.

“Flies in the head,” my mother continues. “Dhora pad gaya! This daughter of mine. When will you be subdued?”

A fly finds its way near my left earlobe. It whirs like an airplane. Will it bite or just whisper? The fly grows louder than my mother’s dismissiveness. The fly tries to venture down an ear shaft, then circles my head. I wave my hand in irritation and blink.

“I have to nap now.” She stirs the pot one last time and puts the wooden spoon down on a green plastic plate on the counter. “Wake me up with tea.”

My mother naps each afternoon. Sometimes, during these afternoon slumbers in a room of pastel green curtains, she dreams. Dreams that reveal. As when a cousin had run away from home, escaping onto a train, disappearing into a crowd. No one told my mother that had in fact happened. When she pressed the matter with a relative, months later, the story spilled forth like a broken necklace. Words like beads slid and bounced on a wooden floor across the room, accompanied by my mother’s requisite gasps.

I crave such dreams, her gift of knowing. Instead, I fall into a black wash of sleep each night, waking each morning, unsure where all the hours have gone.

In Florida, in the back of our house, there is a dock that overlooks the canal that leads a few meters away into the ocean. The ocean shines. Sometimes, it frowns. Rocks, waves, dips, hurtles. It is easy to watch the ocean and realize that both certainty and uncertainty exist side by side. The certainty that the ocean will be there. The uncertainty of its form, its mood. I grow up mirroring the ocean in my mutability, like the stages of a moon that is quarter, half, full. I wait for those nights, partially unexpected, on evening walks through the neighborhood when the moon shines on the ocean, the light shimmering silver on the black water, against a restless wind.

The author and her mother

An idea of belonging.

Listen to Anisa Rahim talk to Mary Ann Koruth about what it means to belong. Their conversation opens with a reference to the Mewati mosque featured in this photograph. The mosque is located in modern day Gurgaon, a suburb of Delhi, where much of Anisa’s extended family lives.

What it means to belong.

On Cows

A poem By Anisa Rahim

Anisa Rahim reads "On Cows"

I would have been a cow, my mother answers

do cows speak and think of one another, of us,

they must

but they move only when slapped by the palm of a hand

derisive click of the tongue, ‘huth,’

when the street throbs with Maruti cars,

scooters, dry air

it is as if they are all alone,

in a field, eating grass,

they might as well be staring at the sky,

the moon hanging from its lip,

you can’t understand,

and she tells me some days later

about the cow she was gifted once,

such big, pretty eyes

her own eyes grow larger as she says this,

she comes into my bedroom years later

to ask if both her eyes are the same shape

yes, of course, leave me alone,

you are so strange

No, one is slightly larger than the other

ten years later, I would look in the mirror

and realize the same thing about my own eyes

God denied us symmetry at birth

but no, it is the beauty of jagged shapes